Leona Douglas

On September 5, 1967, an up-and-coming country music singer took center stage at the Porter Waggoner Show for the first time.[1] With her golden hair piled high into a bouffant and wearing a red sleeveless dress with a matching brooch, Dolly Parton belts out “Dumb Blonde” – a song that, earlier that year, had become her first Billboard charting hit. [2] Dolly Parton was fresh off the release of her first full-length album, titled Hello, I’m Dolly, with Monument Records, and her appearance on the show became a pivotal moment in her meteoric rise to the top of the country music charts.[3] But before Dolly Parton, there was Leona Douglas.

Five years prior to Hello, I’m Dolly, Leona Douglas attempted to jumpstart her career through Monument Records and was working directly with Fred Foster, the man who would eventually sign Dolly Parton to the label. Ms. Douglas’ country career was brief and by the time “Dumb Blonde” began climbing the charts she had already transferred to a new label singing R&B music. However, Leona Douglas’ presence as one of country music’s earliest Black performers and first Black female recording artist cements her place in the story of country music history. Leona Douglas’ was a trailblazer in country music and by analyzing her life, work, and contributions we can better understand appropriate ways her role can be commemorated on the landscape.

[1] Library of Congress, “Dolly Parton and the Roots of Country Music,” Library of Congress, Accessed September 29, 2022, https://www.loc.gov/collections/dolly-parton-and-the-roots-of-country-music/articles-and-essays/dolly-parton-timeline/

[2] Dolly Parton, “Dolly: The Ultimate Collection – Dolly’s First Appearance on The Porter Wagoner Show (1967)”, Posted November 2020, Time Life, 1:16, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5cFiU0ujzE4.

[3] “Dolly Parton,” Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, July 5, 2022. https://www.countrymusichalloffame.org/hall-of-fame/dolly-parton

Douglas Bend

On October 28, 1941, Leona W. Douglas was born to Noel Douglas Sr. and Anna Lena Douglas in Gallatin, Tennessee.[1] According to the 1940 census, Ms. Douglas’ parents rented a home for three dollars a month located at 384 Shute Road.[2] Shute Road no longer exists; however, members of the Douglas family cite Leona Douglas’ birthplace as a farm on Douglas Bend Road which they refer to as “The Shoot.”[3] Noel Douglas Sr., whose education ended when he left the third grade, worked as a rock mason to provide for his growing family. [4] Anna Douglas reached the seventh grade and, with no listed occupation, likely cared for the children, prepared meals, and completed other daily household tasks. [5] Both Noel and Anna Douglas were born on February 16th; though, Mr. Douglas was twenty-two years her senior.[6] The two married when she was seventeen and he was thirty-nine. Leona Douglas would see the birth of four more sisters. When she was a child, Ms. Douglas worked in the family’s tobacco fields alongside her other siblings.[7] “He made boys out of us,” Leona joked at Noel’s 106th birthday celebration.[8] When she was a teenager, the family moved to her grandparent’s property on Tobacco Valley Road – land that was given to ancestors of the Douglas family after being forced to work the land as slaves.[9]

[1] Obituary of Leona Wylee Douglas-Chambers, The Tennessean (Nashville, TN), August 19, 2003.

[2] U.S. Census Bureau, 1940 United States Federal Census, generated by Danny Harp, using ancestry.com (5 March 2021).

[3] Iona Douglas-Moguel (Leona Douglas’ daughter), social media message to author, 2022.

[4] U.S. Census Bureau, 1940 United States Federal Census.

[5] U.S. Census Bureau, 1940 United States Federal Census.

[6] Lisa Human, “‘Cradle-Robber,’ Bride To Celebrate His 100th,” The Tennessean, February 1984.

[7] Ellen Dahnke, “5 Generations Help Deacon Celebrate 106th Birthday,” The Tennessean, February 1990.

[8] Ellen Dahnke, “5 Generations Help Deacon Celebrate 106th Birthday,” The Tennessean, February 1990.

[9] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

Education

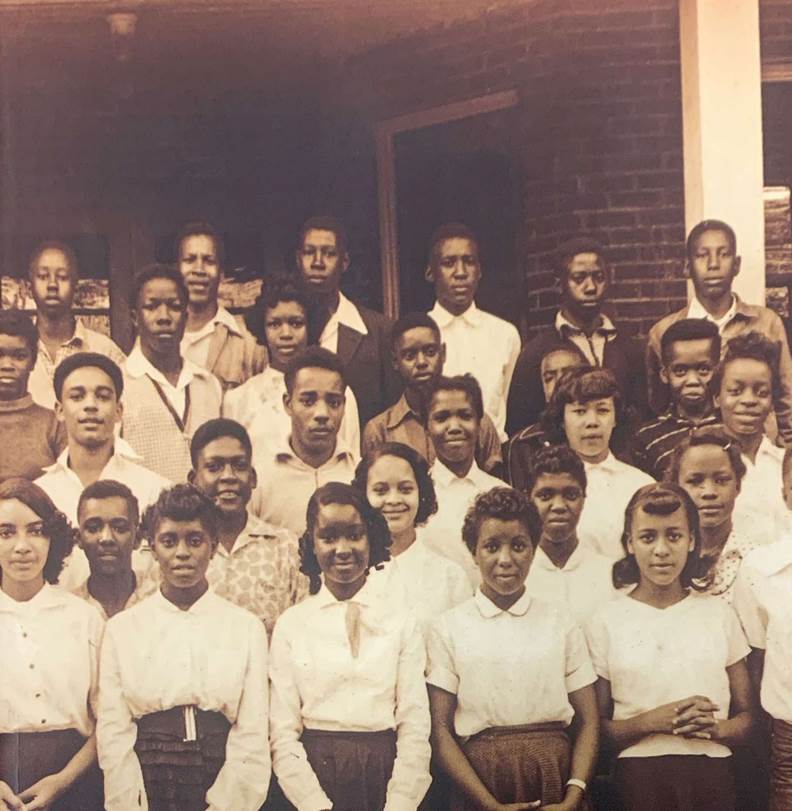

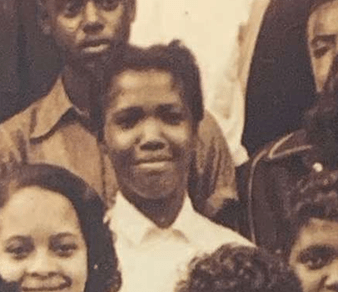

Leona Douglas attended Sumner County Schools prior to the desegregation of public schools. According to Gallatin historians Velma Howell Brinkley and Mary Huddleston Malone, “No one could deny the enormous disparities between Sumner County’s Black and White schools. Black children, some as young as six, walked five or more miles to school, while their White counterparts rode buses . . . New textbooks went to the Whites; their outdated used books were sent to the Black schools.”[1] To get to and from school, Ms. Douglas either walked or joined one of the many community carpools operated by available parents (Figure 1). Until eighth grade, Ms. Douglas attended Union Elementary School located at 260 East Winchester Street. In a photo published in Images of America: African-American Life in Sumner County, Leona Douglas is seen smiling alongside the rest of the eighth-grade class (Figure 2 and 3).[2]

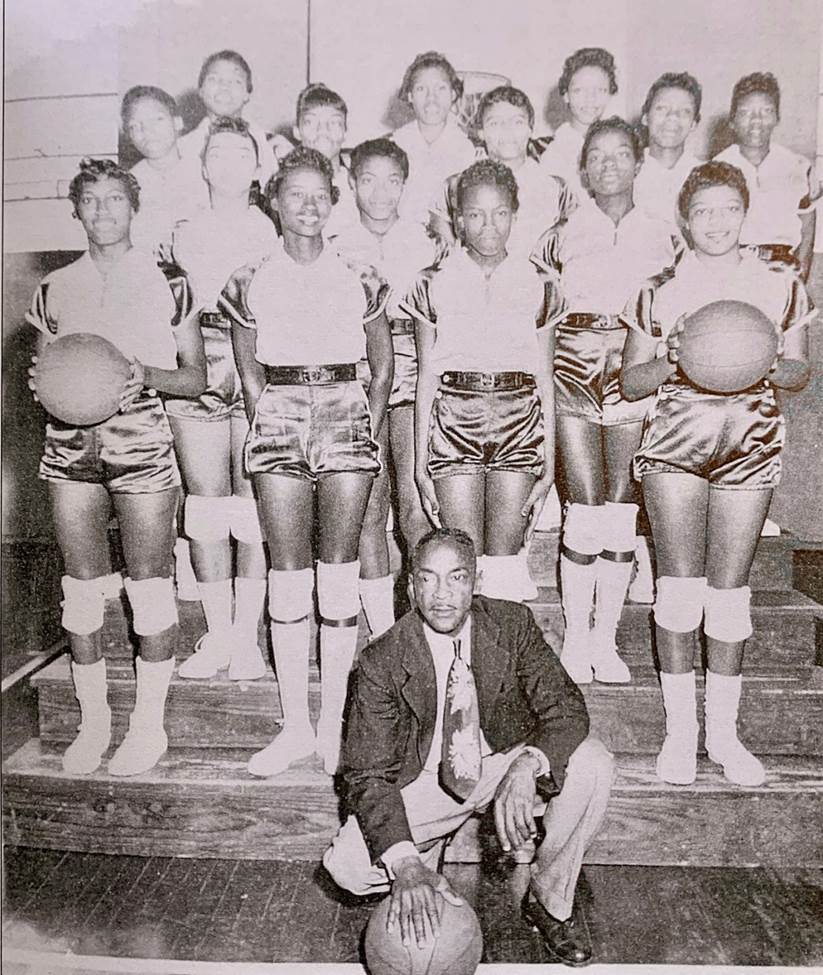

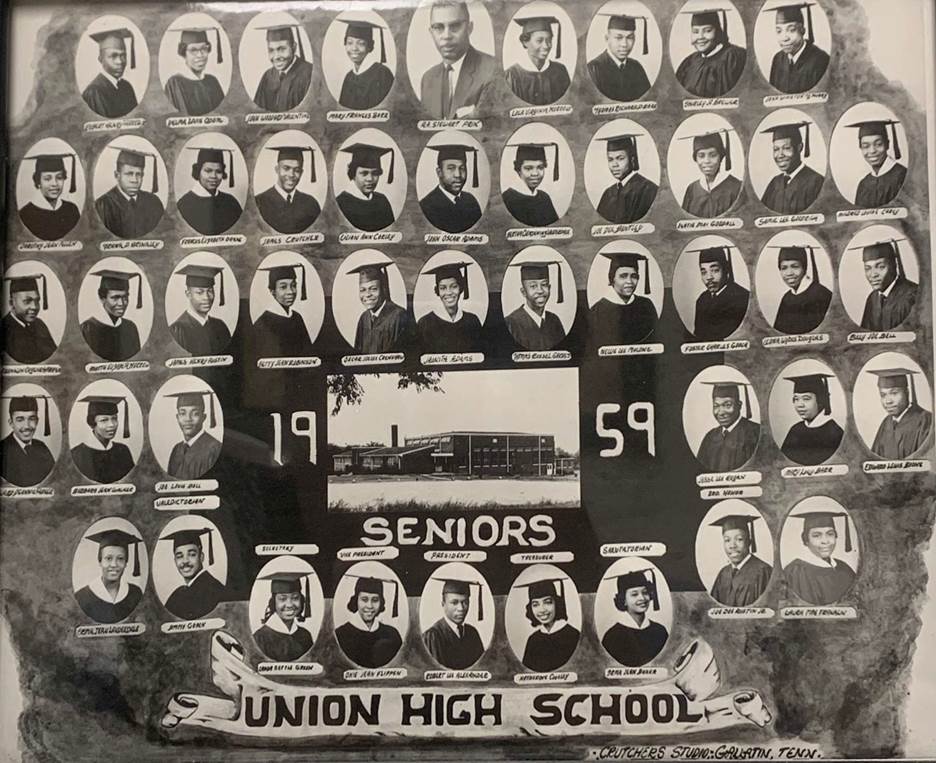

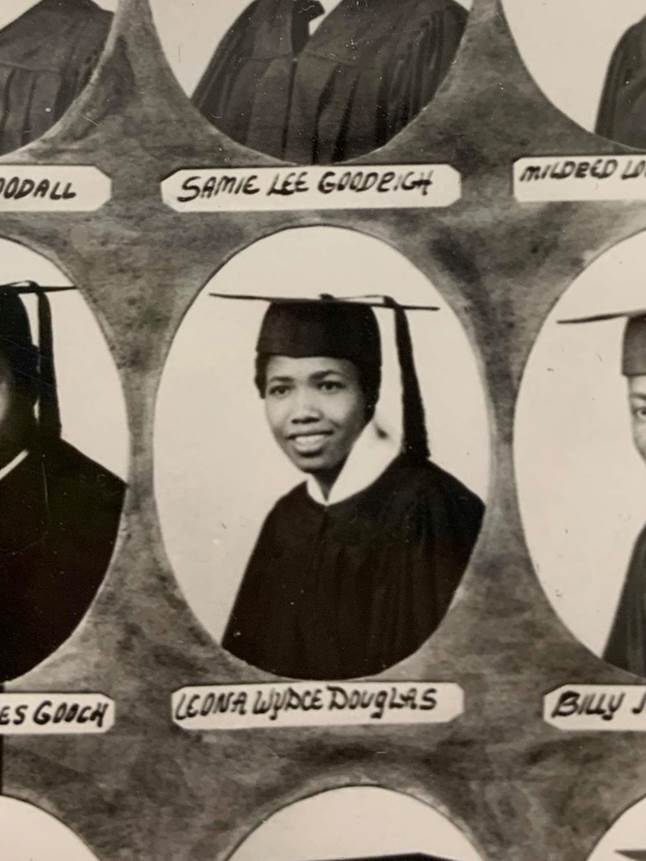

In 1955, Leona Douglas entered high school attending Union High School, Sumner County’s “first and only high school for Black students.” [3] Opened just four years prior in 1951, Union High School was located at 600 Small Street.[4] During her time at Union High School, like many other students, Ms. Douglas was involved in extracurricular activities outside of her classes. Georgia Wright, who attended Union one year behind Ms. Douglas, recalled singing alongside her in the high school’s chorus.[5] In her senior year, Leona played guard on the school’s girls basketball team (Figure 5), and at that year’s homecoming, she was crowned Queen.[6] In 1959, Leona Douglas graduated from Union High School (Figure 6).

[1] Velma Howell Brinkley and Mary Huddleston Malone, Generations: A Pictorial Journey Into the Lives of African Americans in Sumner County, Tennessee 1796-1996 (Nashville: Morgan Publications, 1996), 45.

[2] Velma Howell Brinkley and Mary Huddleston Malone, Images of America: African-American Life in Sumner County (Nashville: Arcadia Publishing, 1998, 45.

[3] Jen Todd, “Gallatin’s Only Black High School Remembered with Display at Old Union School,” The Tennessean, February 5, 2019, https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/local/sumner/gallatin/2019/02/05/gallatins-only-Black-high-school-remembered-display/2771503002/.

[4] Velma Howell Brinkley and Mary Huddleston Malone, African-American Life in Sumner County, 32.

[5] Georgia Wright (Gallatin Resident), in discussion with the author, Sumner County Museum, September 2022.

[6] Iona Douglas-Moguel (Leona Douglas’ daughter), social media message to author, 2022.

A Golden Star

After high school, Ms. Douglas formed a gospel group called the Golden Stars with two of her sisters, Frances and Laura Douglas, and one of her closest friends, Nellie Rutherford (Figure 7). According to Laura Douglas, Noel and Anna Douglas refused to allow their daughters to sing anything but gospel music, as they were deeply religious family. The group traveled to area churches singing gospel standards and were on track to record with country music songwriter Boudleaux Bryant. Leona Douglas decided to break with the group and, in opposition to her parents, record as a solo country and western artist.[1]

[1] Laura Douglas (Leona Douglas’ Sister), in discussion with the author, September 2022.

“Country Product Surging”

In the November 10, 1962, issue of Billboard Music Week, Nashville’s country music scene took center stage. The front-page article was entitled “Country Product Surging on Charts and More Coming Up.” It read, “A continued strong showing on the charts and a volume of new release material characterized the country music scene last week as the trade prepared to help WSM observe its 11th Annual Country Disk Jockey Festival at its Nashville home base.”[1] That November week saw a near record breaking number of country and western releases with “all companies looking forward to the opportunity to play new disks for WSM visiting deejays on the juke boxes.”[2] Simultaneously, country artists like Hank Snow, Bill Anderson, and Brenda Lee were creeping up the pop charts.[3] Country and western music was growing and reaching new audiences, and Nashville was becoming “broadly identified” by its unique sound.[4] It was this same week that Leona Douglas released her first two singles with Monument Records.[5]

[1] Ren Grevatt, “Country Product Surging on Charts ad More Coming Up,” Billboard Music Week, November 1962.

[2] Ren Grevatt, “Country Product Surging on Charts ad More Coming Up,” Billboard Music Week, November 1962.

[3] Ren Grevatt, “Country Product Surging on Charts ad More Coming Up,” Billboard Music Week, November 1962.

[4] Pat Twitty, “Nashville Says It Always Has ‘Sound’,” Billboard Music Week, November 1962.

[5] “Spotlight Singles of the Week,” Billboard Music Week, November 1962.

Meeting Fred Foster

Leona Douglas’ journey to her first single began when she met Fred Foster. Fred Foster, “a soft-spoken man who was always immaculately dressed,” founded Monument Records in 1958 moving the label to Nashville in 1960. [1] That same year, Foster signed Roy Orbison whose first hit “Only The Lonely (Know How I Feel)” made Orbison “a top-selling international artist who greatly heightened Nashville’s visibility as a music center.”[2] Ms. Douglas and Fred Foster met sometime between her graduation from high school in 1959 and 1962 likely introduced by Ms. Douglas’ manager, Hal Gilbert.[3] In an interview with Iona Douglas-Moguel, Leona Douglas’ daughter, Fred Foster recalled, “They said, ‘You know it will be hard to get her played’ . . . I never thought of that. Never dawned on me. I mean, [if] we make a good record, it ought to get played.”[4]

[1] Jennifer Bruce and Tena Lee, Southern Music Icons of Hendersonville, Tennessee (Charleston: The History Press, 2022), 30.

[2] “Fred Foster,” Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, July 5, 2022. https://www.countrymusichalloffame.org/hall-of-fame/fred-foster.

[3] Iona Douglas-Moguel, “Tobacco Valley,” (unpublished manuscript, 2014), typescript.

[4] Fred Foster (Founder of Monument Records), in discussion with Iona Douglas-Moguel, Fred Foster’s home, prior to 2019.

“Too Many Chicks” and “Jealous Heart”

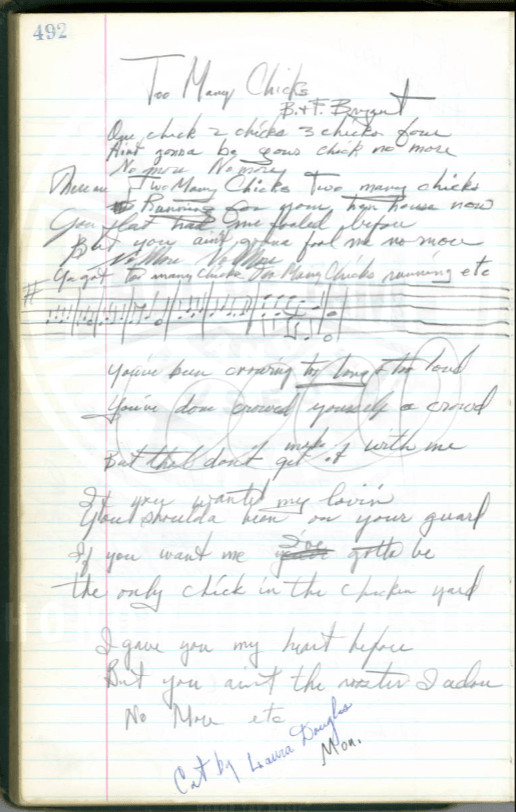

In 1962, Leona Douglas recorded two tracks and released them on a single 45. The record’s A-side track was “Too Many Chicks” which later “became a hit.”[1] “Too Many Chicks” was written by acclaimed songwriting duo Boudleaux and Felice Bryant who “are widely considered to be the first to move to [Nashville] in order to make a living solely as songwriters.”[2] The song’s handwritten manuscript is now a part of the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum’s archives (Figure 8). Prior to 1962, the duo had written many hits for other artists including “Country Boy” recorded by Little Jimmy Dickens in 1949 and “Wake Up, Little Susie” recorded by the Everly Brothers in 1957.[3]

The B-side track of the record was “Jealous Heart” – a song that had been a hit for country artist Tex Ritter two decades earlier.[4] “Jealous Heart was penned by Jenny Lou Carson who “became one of country music’s pioneering female songwriters.”[5] Carson is known as “the first female to write a number one country hit.”[6] During the week of their release, “Too Many Chicks” and “Jealous Heart” appeared on Billboard Music Week’s Spotlight Single of the Week a column that listed records with the “strongest sales potential of all records reviewed” in a single week.[7] The record received three stars, a ranking that categorized the two tracks as having “moderate sales potential.”[8]

Before a records release, Fred Foster and his small staff would either gather in “Foster’s plush, darkly paneled office or the large conference room” to stuff records into envelopes to be sent off to radio stations.[9] Louis Oliver III, now a Sumner County Chancery Court Judge, worked for Monument Records “running errands” near the time that Ms. Douglas was signed to the label. [10] He recalled, “We’d send to certain disc jockeys first . . . Some would go out air mail special delivery, and they would get there two or three days earlier and the disc jockeys would start playing them right away.”[11] showsFred Foster utilized his connections with WSM and WLAC radio stations to promote the record; however, he did not disclose to deejays that the woman singing the song was African American.[12] In another attempt to promote Leona Douglas, Foster would add her to the lineup of shows without disclosing her race to event promoters and without adding her name to the venue’s marquee or any promotional materials. [13] This tactic is what he referred to as “ghosting” Ms. Douglas. Iona Douglas-Moguel recalls, “he said that he had to ghost her because she was before her time . . . He wanted the world to know her based off of her voice and not the content of her skin.”[14] However, the release and subsequent promotion places Leona Douglas at a crux of country music history.

[1] Tennessee State Museum exhibit The State of Sound: Tennessee’s Musical Heritage

[2] Jennifer Bruce and Tena Lee, Southern Music Icons of Hendersonville, Tennessee (Charleston: The History Press, 2022), 25.

[3] “Boudleaux and Felice Bryant,” Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, July 5, 2022. https://www.countrymusichalloffame.org/hall-of-fame/boudleaux-and-felice-bryant

[4] “Tex Ritter,” Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, July 5, 2022. https://www.countrymusichalloffame.org/hall-of-fame/tex-ritter

[5] “Jenny Lou Carson,” Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame, accessed October 18, 2022, http://nashvillesongwritersfoundation.com/Site/inductee?entry_id=723#:~:text=She%20was%20mentored%20by%20songwriting,Ernest%20Tubb%20and%20other%20headliners.

[6] Jerry Langley and Arnold Rogers, Many Tears Ago: The Life and Times of Jenny Lou Carson (Nashville: Nova Books, 2005), 1.

[7] “Spotlight Singles of the Week,” Billboard Music Week, November 1962.

[8] “Spotlight Singles of the Week,” Billboard Music Week, November 1962.

[9] Jennifer Bruce and Tena Lee, Southern Music Icons of Hendersonville, Tennessee (Charleston: The History Press, 2022), 29.

[10] Jennifer Bruce and Tena Lee, Southern Music Icons of Hendersonville, Tennessee (Charleston: The History Press, 2022), 28.

[11] Jennifer Bruce and Tena Lee, Southern Music Icons of Hendersonville, Tennessee (Charleston: The History Press, 2022), 29.

[12] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[13] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[14] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

First

Archival evidence, music charts, and recordings prove that Leona Douglas-Chambers was one of the earliest African American women to pursue country and western music, but some historians and institutions say she was the first. According to historians Bobbie Malone and Bill C. Malone, “Released in 1962, four years before Charley Pride made his first recordings for RCA Victor, “Too Many Chicks” may merit recognition as the first country song to be released by an African American singer in the modern era.”[1] In an exhibit titled The State of Sound: Tennessee’s Musical Heritage, the Tennessee State Museum called Leona Douglas, “the first African American woman to record for a country music record label.”[2] The Country Music Hall of Fame lists Ms. Douglas’ release as, “the first country music record recorded by an African American Woman.”[3]

In the same year that Leona Douglas released her two tracks, Esther Phillips “deployed country music to break out of the confines of R&B radio and reach a pop audience,” with her recording of Eddie Miller’s country standard Release Me.[4] According to historian Pamela E. Foster, “The song went to the pop and R&B charts for Phillips, peaking at number eight and number one respectively. Buoyed by the song’s success, Phillips released a full country album in 1963.” Though Phillips’ release was a country track, she had previously established herself as an R&B artist still making Leona Douglas’ presence exclusively as a country and western artist unique. In the early 1960s, country crossovers from African American R&B artists, like Phillips, were becoming more common with many covering “country songs to establish the authenticity of their artistic personae and to reference not only their own southern roots, but also the larger, shared experience of the Great Migration and the cultural and social changes that attended it.”[5] Though Ms. Douglas’ initial release was moderately successful, it would be her last release with Monument Records and, by 1965, she was recording on a new label.

[1] Bobbie Malone and Bill C. Malone, Nashville’s Songwriting Sweethearts: The Boudleaux and Felice Bryant Story (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2020), 98.

[2] Tennessee State Museum exhibit The State of Sound: Tennessee’s Musical Heritage

[3] Boudleaux and Felice Bryant Songwriting Ledger #6 of 16, 1960, Boudleaux and Felice Bryant Songwriting Manuscript Collection, Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, Nashville, Tennessee.

[4] Diane Pecknold and Kristine M. McCusker, Country Boys and Redneck Women: New Essays in Gender and Country Music (Jackson: The University Press of Mississippi, 2016), 148

[5] Diane Pecknold and Kristine M. McCusker, Country Boys and Redneck Women: New Essays in Gender and Country Music (Jackson: The University Press of Mississippi, 2016), 148

Shifting Sounds

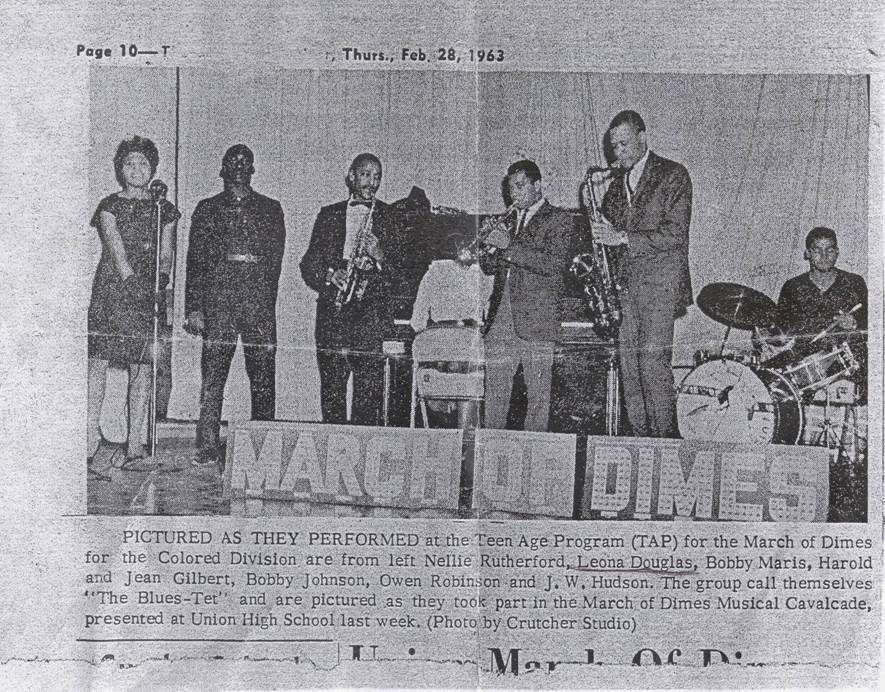

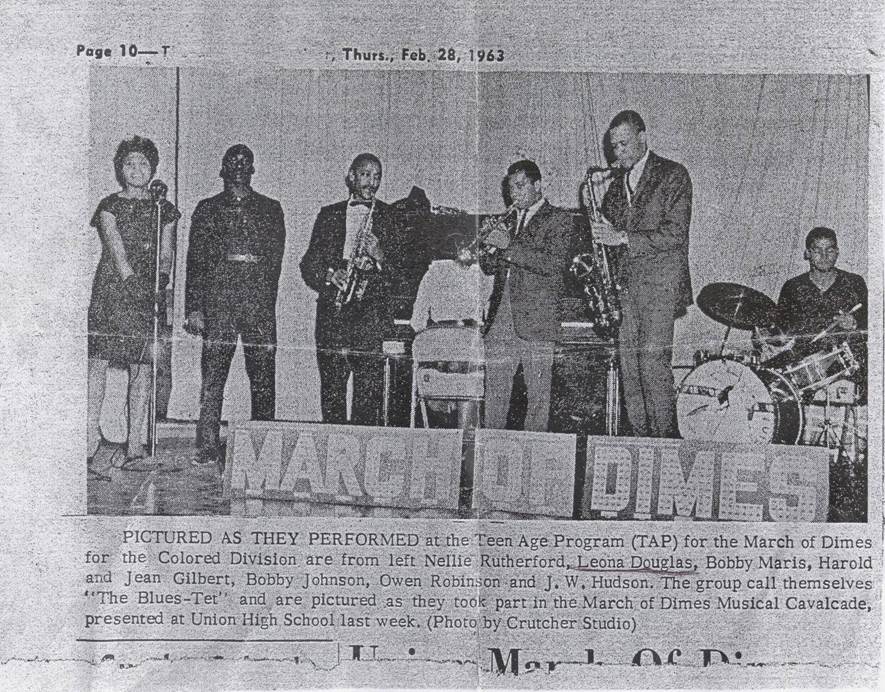

In February of 1963, Leona Douglas walked onto the stage at Union High School to perform in the Teenage Program in support of the March of Dimes. Ms. Douglas grabbed the microphone stand in front of her as a photographer snapped an image that was later published in a local newspaper (Figure 9). Performing as a member of a group called The Blues-Tet, this moment marked one of her earliest performances as a R&B artist, transitioning away from country and western music. Soon after, Leona Douglas joined Southern City Records, a record label founded by Ms. Douglas’ longtime manager, Harold Gilbert, and his wife, Jean Gilbert.[1] Returning to Gallatin, Tennessee, Ms. Douglas was represented by Harold and Jean Gilbert’s adjoining agency Hittsburgh Music Company. [2]

Figure 9. Leona Douglas performs in a group called “The Blues-Tet.” (Crutcher Studio, February 28, 1963.)

In 1965, Leona Douglas released her second record which featured, on its A-side, a track titled “The Greatest Lover Girl In The World” and on its B-side the song “‘Till I Get In Someone’s Arm’s.”[3] Leona Douglas recorded under the name Leona Wyleese, using a variation of her middle name. Harold Gilbert’s family was directly involved with Southern City Records. His wife was his primary collaborator, and his sisters were involved in writing songs. “The Greatest Lover Girl In The World” was co-written by Harold Gilbert and his sister, Yvonne Gilbert, and “‘Till I Get In Someone’s Arm’s” was co-written by Harold Gilbert and his other sister, Janie West. Copies of Ms. Douglas’ Southern City record are rare. Leona Douglas was listed on Billboard’s 1967 International Record Talent Directory published ahead of the new year on December 24, 1966.[4] Within the registry, Harold Gilbert was listed as her manager, Southern City listed as her Label, and she was represented holistically by Hittsburgh Talent Agency. [5]

As an R&B artist, Leona Douglas performed on the popular music variety show Night Train alongside Aretha Franklin, something she briefly recalled to her daughter, Iona Douglas-Moguel. “When I was little like that, I did not know what she was talking about, and I found out later that . . . she was on a television show in Nashville called Night Train. I was little. I didn’t understand it. But she was trying to describe what she looked like and [the] wig she had on.”[6] Night Train premiered in 1964 and “featured some of Nashville’s best R&B musicians backing some of the city’s finest singers and out-of-town stars.”[7] Few recordings of the show exist as they were thrown out by the television studio that replaced WLAC-TV. [8] In 1968, Leona Douglas left music and moved, with her son Ivan and daughter Inez, from the family’s property on Peach Valley Road to Cumberland View apartments, a complex nicknamed “Dodge City” because of frequent shootings.[9]

[1] Velma Howell Brinkley and Mary Huddleston Malone, Generations: A Pictorial Journey Into the Lives of African Americans in Sumner County, Tennessee 1796-1996 (Nashville: Morgan Publications, 1996), 130.

[2] Velma Howell Brinkley and Mary Huddleston Malone, Generations: A Pictorial Journey Into the Lives of African Americans in Sumner County, Tennessee 1796-1996 (Nashville: Morgan Publications, 1996), 130.

[3] Wyleese, Leona. The Greatest Lover Girl In The World and ‘Till I Get In Someone’s Arm’s. 1965. Southern City Records, vinyl.

[4] “1967 International Record Talent Directory,” Billboard, December 1966, 85.

[5] “1967 International Record Talent Directory,” Billboard, December 1966, 85.

[6] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[7] “Night Train to Nashville: Music City Rhythm & Blues 1945-1970 Part II,” Google Arts and Culture, Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, Accessed October 1, 2022, https://artsandculture.google.com/story/night-train-to-nashville-music-city-rhythm-blues-1945-1970-part-ii-country-music-hall-of-fame/YwWR6RXbHFr8KA?hl=en.

[8] Michael Gray (Executive Senior Director of Editorial and Interpretation, Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum), phone discussion with the author, 2020.

[9] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

A New Life

After moving to Nashville, Ms. Douglas began working at Genesco – a shoe manufacturing plant located on Murfreesboro Road – where she joined other factory workers in assembling primarily men’s dress shoes.[1] During this time, Genesco was at its height employing thousands of individuals across the company’s twelve factories. This made Genesco among Tennessee’s largest employers.”[2] In March of 1968, Ms. Douglas was on break, smoking a cigarette outside the factory, when she went into labor.[3] On March 27, 1968, she gave birth to her third child, Iona Douglas.

After leaving music, Leona Douglas only shared stories that alluded to her previous career and Iona grew up never fully knowing about her mother’s past. [4] In one of her earliest memories of her mother, Iona recalled hearing her mother singing gospel with her sisters on WLAC, a local radio station. “We would be sitting in the car and have the radio station on, and we could hear them on the radio singing . . . Back in those days the seat was long across. I can remember all of us, me and my other sister, were all sitting in the front seat and we were just jamming knowing that that was my mom.” [5] Some programs on WLAC would switch from R&B to gospel on Sundays, including John Richbourg’s “Ernie’s Record Parade” whose Sunday night show was “strictly gospel.”[6]

While raising her three children, Ms. Douglas continued to work at Genesco. “She put all her life into Genesco,” Iona remembered. [7] Ms. Douglas relied on the city’s public transportation services to get to and from work which meant early mornings and a long commute.[8] “She had to get up early, get on a bus [that took] her downtown to transfer over to another bus that [took] her out [to] Murfreesboro Road. She did that for 20 years.”[9] Ms. Douglas had the job of assembling the soles of the shoes that were being made within the factory – a process that required the application of glue that, by the end of the day, would cover her hands and drip down her legs.[10] “Every day she would come home, and the glue would be all over her hands [and] all on her legs,” Iona remembered.[11] During moments of leisure, the family would gather around a shared stereo and listen to music. “We had this stereo with a TV in the middle. You lift it up and it has a stereo inside and you put the 45s in it and play it like that . . . We had everybody, Motown – just every type of music that was out there. She had a whole collection, and she danced around with us.”[12]

For the Douglas family, Sunday meant traveling thirty miles to attend services at Peach Valley Missionary Baptist Church, where Leona sung in the choir. “It was like a family church . . . Grandmother taught Sunday School. My grandfather was the Deacon of the church. My mother was part of the choir. My aunts led the choir. And it was just like a family thing all the way around.”[13] The family traveled to Peach Valley three times a week – on Wednesday nights for bible study, Saturday for choir practice, and Sunday for routine services.[14] Sunday morning services were followed by Sunday lunch at the family’s nearby property. Iona recalled, “It was just a family affair every Sunday and everybody would bring their own meal. We had one big, long table and everybody would put all their food out and everybody would just feed themselves. It was like Christmas and Thanksgiving every Sunday.”[15] The adults sat at a long table in the middle of the kitchen while the children dined under the house’s adjoining carport, until the completion of an extension of the home in 1978 that offered extended indoor seating.[16] “The kids’ table was just as long as the adult table.” [17] Iona especially enjoyed spending time with her cousins, of which she had dozens. Iona distinctly recalled unsuccessfully trying to hold back laughter as her cousins would make jokes during the family’s pre-meal prayer. “We would just bust out laughing” [18] Every week, Sunday would begin around 7:00 AM and finally wrap up after a family dinner that followed evening services.

In 1972, Leona Douglas married William Allen Chambers becoming Mrs. Leona Douglas-Chambers[19] William Chambers, nicknamed “Steel Bill,” lived in Gallatin, Tennessee. When the couple married, Mr. Chambers moved, with three of his four children, to Nashville to live with Ms. Douglas and her children. Needing additional space, both families moved into a larger apartment in the Cumberland View complex. [20]

Though the new apartment ushered in many changes, it offered Leona Douglas-Chambers more room to help others in need. “She would give the shirt off her back. She would bring the homeless into our home.”[21] Iona Douglas-Moguel recalls one man in particular who could be seen throughout the year walking the streets; however, on Thanksgiving and Christmas would share the day with the Douglas-Chambers family. [22] “He would come at 5:00 AM in the morning and she would feed him breakfast, lunch, and dinner.”[23] At each meal, the children were instructed to help him prepare his plate. “It taught us that, [homelessness] is real . . . It showed us how to humble ourselves because this could be Jesus Christ. She used to say that all the time. ‘You never turn your back on anyone. That could be Jesus Christ.’”[24]

Once all of her children turned eighteen and began to pursue their own career aspirations, Leona Douglas-Chambers entered college.[25] Ms. Douglas-Chamber’s shift away from shoe manufacturing came at a time when the rise of casual fashions, growing popularity of athletic shoes, and the increase in the global outsourcing of manufacturing jobs led to the closure of many of Genesco’s factories.[26] After receiving her degree, Mrs. Douglas-Chambers began working as an assistant to Dr. Dorothy Lavinia Brown.[27] According to the National Library of Medicine, “Dr. Dorothy Lavinia Brown spent her childhood in an orphanage and grew up to become the first African American woman surgeon in the South, eventually being made chief of surgery at Nashville’s Riverside Hospital. She was also the first African American woman to be made a fellow of the American College of Surgeons.”[28] Leona Douglas-Chambers worked for Dr. Brown until she made the decision to retire.[29]

Peach Valley Missionary Baptist Church remained an important part of Leona Douglas-Chambers’ life. Every year, Leona Douglas-Chambers and her entire family would gather at the Gallatin church to celebrate their parent’s joint birthdays.[30] In 1990, The Tennessean published an article titled “Five Generations Help Deacon Celebrate 106th Birthday.” In the article, writer Ellen Dahke wrote, “Douglas’ birthday has come to be not only an annual event, but a grand affair bringing together the rural congregation he considers family and five generations of his natural family.”[31] Noel Douglas, Sr. passed away the following September.[32]

On August 19, 2003, after a long battle with cancer, Leona Douglas-Chambers passed away at Sumner Regional Medical Center.[33] Once again, the family shuffled into the plush, red pews of Peach Valley Missionary Baptist Church to pay their respects.[34] Leona Douglas-Chambers was buried at Sumner Memorial Gardens in Gallatin, Tennessee.

Iona Douglas-Moguel only learned of her mother’s country music career after her death and that revelation that inspired her to learn more about her family’s past.[35] “I had to know the story . . . I needed to know the truth.” [36] Utilizing the stories her mother told her and the research she collected from other primary and secondary sources, Iona Douglas-Moguel has written a movie script that has since developed into a multi-season series detailing her mother’s life and the dramatic aftermath of her mother’s death that uncovered family secrets and led to a legal fight for the family’s Peach Valley property. Iona Douglas-Moguel continues to protect and preserve her mother’s legacy.

[1] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[2] Bill Carey, “Genesco,” The Tennessee Magazine, December 28, 2017, https://www.tnmagazine.org/genesco/.

[3] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[4] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[5] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[6] Randy Fox, “A New Box Set Revives The Glory of Nashboro Records,” Nashville Scene, December 2013.

[7] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[8] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[9] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[10] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[11] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[12] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[13] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[14] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[15] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[16] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[17] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[18] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[19] Sumner County, Tennessee, marriage certificate no. 389, 1972, William Allen Chambers and Leona Wylce Douglas; County Clerk, Sumner County.

[20] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[21] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[22] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[23] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[24] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[25] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[26] Bill Carey, “Genesco,” The Tennessee Magazine, December 28, 2017, https://www.tnmagazine.org/genesco/.

[27] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[28] “Changing the Face of Medicine: Dorothy Lavinia Brown,” U.S. National Library of Medicine (National Institutes of Health, June 3, 2015), https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_46.html.

[29] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[30] Ellen Dahnke, “5 Generations Help Deacon Celebrate 106th Birthday,” The Tennessean, February 1990.

[31] Ellen Dahnke, “5 Generations Help Deacon Celebrate 106th Birthday,” The Tennessean, February 1990.

[32] Obituary of Noel Douglas, The Tennessean (Nashville, TN), September 3, 1990.

[33] Obituary of Leona Wylee Douglas-Chambers, The Tennessean (Nashville, TN), August 19, 2003.

[34] Obituary of Leona Wylee Douglas-Chambers, The Tennessean (Nashville, TN), August 19, 2003.

[35] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.

[36] Iona Douglas-Moguel, oral history to Danny Harp, virtual, April 26, 2021.