Eugenia Jo Ann Sweeney

‘Twas batter and scarred, and the auctioneer

“The Touch of the Master’s Hand” By Myra Brooks Welch[1]

Thought it scarcely worth his while

To waste much time on the old violin,

But held it up with a smile

“What am I bidden, good folks,” he cried,

“Who’ll start the bidding for me?”

“A dollar, a dollar”; then “Two! Only two?

Two dollars, who’ll make it three?

Three dollars, once, three dollars, twice;

Going for three –” But no,

From the room, far back, a gray-haired man

Came forward and picked up the bow;

Then, wiping the dust from the old violin,

And tightening the loose strings,

He played a melody pure and sweet

As a caroling angel sings.

The music ceased, and the auctioneer,

With a voice that was quiet and low,

Said: “What am I bid for the old violin?”

And he held it up with the bow.

“A thousand dollars, and who’ll make it tow?

Two thousand! And who’ll make it three?

Three thousand, once’ three thousand, twice,

And going, and gone,” he said.

The people cheered, but some of them cried,

“We do not quite understand

What changed its worth.” Swift came the reply:

“The touch of a master’s hand.”

And many a man with life out of tune,

And battered and scarred with sin,

Is auctioned cheap to the thoughtless crowd,

Much like the old violin.

A “mess of pottage,” a glass of wine;

A game – and he travels on.

He is “going” once, and “going” twice,

He’s “going” and almost “gone.”

But the Master comes, and the foolish crowd

Never can quite understand

The worth of a soul and the change that’s wrought

By the touch of the Master’s hand.

“The Touch of the Master’s Hand” is a poem first published in the February 26th, 1921 issue of The Gospel Messenger. For 15 years no one knew the identity of its author, and the poem was repeatedly printed listing the author as anonymous. It was not until 1936 that Myra Brooks Welch was finally recognized as the poem’s author in a serendipitous series of events where the poem was recited at a conference her son just happened to be attending. For Welch, poetry was her only outlet after arthritis left her confined to a wheelchair and with limited mobility in her hands. Welch, a well-loved pianist and guitarist, was unable to play music and found the best way to express herself in poetry – words she “typed painstakingly using the eraser ends of two pencils.” [2] In her lifetime, Welch published many works, but “The Touch of the Master’s Hand,” gained great popularity; however, Welch earned little to no money for it.[3] With the work’s international success, it is no surprise that it found its way to the desk of Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, at the time a junior high school student.

Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney was familiar with the stage, at least the small stage of her family’s church. When approached by her drama club teacher to participate in a performance competition, Sweeney agreed. Unsure what to recite, her teacher chose “The Touch of the Master’s Hand.” Sweeney had played the violin from a young age so a poem about an “old violin” made sense, and she practiced every day leading up to the competition. The day of the competition, Sweeney stood, hands shaky and palms sweaty, and recited the poem she had meticulously practiced time and time again. As she recited the last line, she lifted her head toward the audience and was met with triumphant applause. Some members of the audience wiped tears from their faces. A smile lit up Ms. Sweeney’s face as pride welled up inside her.[4] This was not her first time on stage, and it wouldn’t be her last. She won second place. This moment didn’t change her life nor was it particularly important in a list of many personal and career accomplishments. In hours of interviews, she only mentioned it briefly.

However, the poem represents a moment of foreshadowing for Sweeney’s life. Sweeney believed that her life was “touched by the Master’s hand” and she had been divinely given gifts that she saw as a vocation more than a passion.[5] Utilizing these gifts, Sweeney made important contributions to the world of recorded music including her groundbreaking work as one of the earliest Black females to record country music. Like Welch, Ms. Sweeney would walk away from her work earning little money and little recognition. Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney’s work in country music recording has gone largely unrecognized by historians and the music industry for over fifty years. Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney had limited commercial success as a country music artist; however, her presence in the country music landscape during the 1970s blazed a trail for future African American recording artists. To understand Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney’s contribution, we have to return to where it all started – in a single story, four-bedroom home in North Nashville.

[1] Wendy Mcfadden, The Story Behind The Touch of the Master’s Hand (Elgin, IL: Brethren Press, 1997), 10-30.

[2] Wendy Mcfadden, The Story Behind The Touch of the Master’s Hand, 36.

[3] Wendy Mcfadden, The Story Behind The Touch of the Master’s Hand, 38.

[4] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[5] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

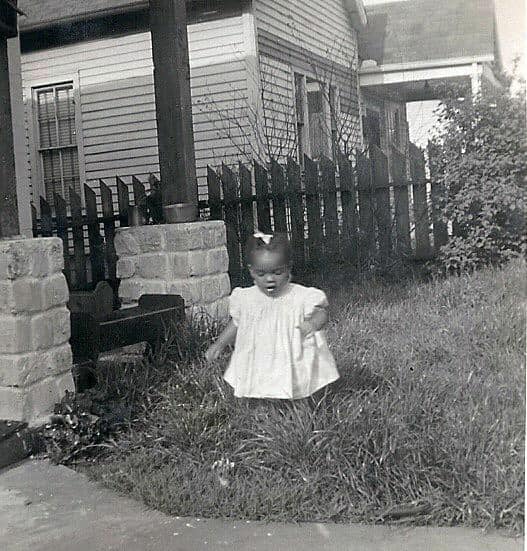

Scovel Street

Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney was born to Elsie Ms. Sweeney Sweeney and James “Jimmy” Sweeney Jr. on January 19, 1954. They brought her home to 2518 Scovel Street (Figure 11), nestled in the heart of North Nashville, one block away from Jefferson Street, the epicenter of African American commerce and entertainment in Nashville during this era.[1] Ms. Sweeney had four brothers with three older brothers and one younger brother making Ms. Sweeney her parents only daughter. When asked about her siblings, Ms. Sweeney said, “If you can imagine being the only girl in a house full of boys, I was a spoiled brat. My father made sure that I was spoiled . . . I was the only girl and next to the baby, so it made things pretty special for me.”[2]

[1] Bobby L. Lovett, Linda T. Wynn, and Caroline Eller, Profiles of African Americans in Tennessee: Second Edition (Nashville: Tennessee State University, 2021), 135.

[2] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

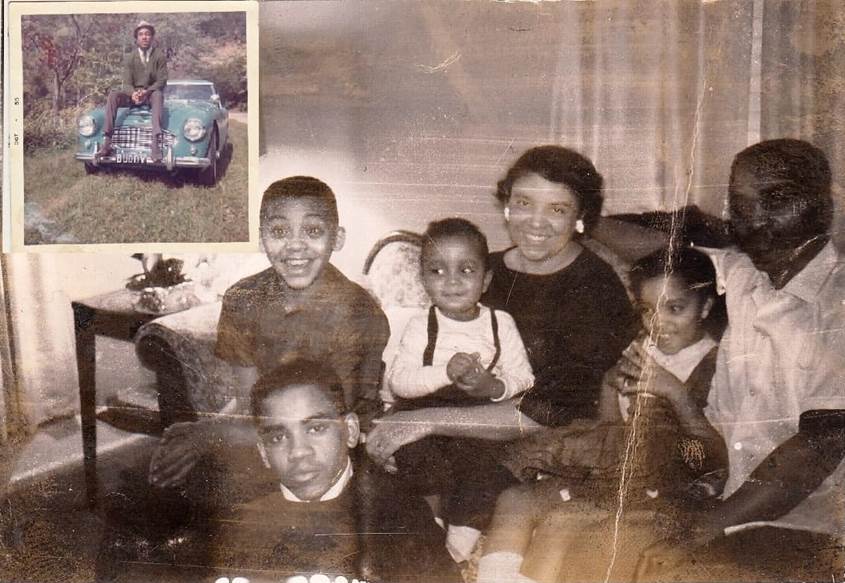

Family

Ms. Sweeney’s father, a U.S. Army Veteran, worked full-time as a postal worker and practiced carpentry. Prior to Ms. Sweeney’s birth, her father was a singer-songwriter trying to make the next big hit amongst other artists in Nashville’s Black music scene. Though James Sweeney never had a record that catapulted him to stardom he did record what some historians call the “most influential demo recording in rock ‘n’ roll history.[1] In June of 1954, Elvis Presley was given James Sweeney’s demo of a song titled “Without You.” According to writer Matthew Leimkuehler, “From that moment, the yearning pop ballad played on 10-inch acetate record helped shape Presley’s aching rock ‘n’ roll delivery.”[2] James abandoned his music career in the early 1960s, but he continued to pen songs throughout Ms. Sweeney’s life. In 2021, Ms. Sweeney told The Tennessean, “There were a group of African American entertainers that came through the back door so we could walk through the front. And he just happened to be one of them.”[3]

Elsie Sweeney, Ms. Sweeney’s mother, worked for Nashville-based shoe manufacturing company Genesco during the earliest years of Ms. Sweeney’s life. Sometime in the mid- to late-1950s, Elsie Sweeney was recruited by Meharry Medical College to join a trainee program, a decision that led her to employment as a Mental Health Assistant at the facility. In this role she helped patients understand their treatment plans and manage their prescriptions. She found professional contentment and enjoyed the opportunity to help others.[4]

Ms. Sweeney understood early her parent’s commitment to their community and helping others. On this topic, Ms. Sweeney said, “Both my parents seemed born to help people. They were both very much alike in that arena. They loved helping people and meeting needs. They were very needs-oriented people.”[5] Ms. Sweeney’s earliest musical memories were provided by her parents, and their early recognition of Ms. Sweeney’s potential and investment in growing her talent changed the trajectory of her life.

Figure 12. Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney is pictured alongside her family. (Michael Kevin Neal, Personal photograph, “Family Photo” Date unknown.)

Figure 13. Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney is pictured posing alongside two of her brothers. (Michael Kevin Neal, Personal photograph, “Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney embracing her brothers,” Date unknown.)

[1] Matthew Leimkuehler, “Meet Jimmy Sweeney, the Nashville singer who influenced Elvis Presley,” The Tennessean (Nashville, TN), January 27, 2021.

[2] Matthew Leimkuehler, “Meet Jimmy Sweeney, the Nashville singer who influenced Elvis Presley.”

[3] Matthew Leimkuehler, “Meet Jimmy Sweeney, the Nashville singer who influenced Elvis Presley.”

[4] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[5] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

A Musical Upbringing

When Ms. Sweeney was three, her father bought the family’s first piano. Ms. Sweeney was mesmerized and would sit, legs dangling from the piano’s stool, just placing her fingers randomly listening to the varying notes ringing from the instrument. Ms. Sweeney’s parents enrolled her in piano lessons soon after, and after she had mastered the basics of the piano, at the age of seven, Ms. Sweeney picked up her first violin. Throughout her life, Ms. Sweeney’s parents were her biggest supporters. As Ms. Sweeney stated, “They thought I could all but walk on water.”[1] Ms. Sweeney continued to play the piano and the violin, in some capacity, for the rest of her life.

Ms. Sweeney’s early relationship with music was not solely related to the instruments she played and practiced every day but is partially a result of her entire family’s appreciation for a broad range of musical genres and styles. Ms. Sweeney describes a household environment where there was always a record spinning. Ms. Sweeney recalled listening to everything from country music to classical, from gospel to rock ‘n’ roll, but, as Ms. Sweeney said, “the Motown artists were by far my favorite.”[2] Ms. Sweeney’s parents made sure that she had access to all the music she loved. As Ms. Sweeney stated, “I’d hear a song on the radio, and my dad and I had a deal that if I did well during the week, didn’t get in any trouble, I could give him a list of 45s.”[3] Her father would take Ms. Sweeney’s list to the local record store on Jefferson Street and pick up every record that she had requested. When asked if the family shared a record player, Ms. Sweeney laughs and says, “Well, we had one and supposed to be for the family – supposed to! But I took control of it. I got the most use out of it, I’ll put it that way.”[4] These early musical moments are what Ms. Sweeney says made her a well-rounded individual, “I feel very fortunate because of the exposure I was afforded at a very young age, and that I grew to love it and I stuck with it all these years. It makes me more than a one-dimensional person . . . I think it makes me a nicer person.”[5]

On Sundays, the family regularly attended church. When asked if church was influential in her life and upbringing, Ms. Sweeney stated emphatically, “I was practically born on the altar. . . [The Church is] very much a part of who I am. Kind of came with me, like my kidneys and my liver and my heart and pancreas.”[6] Ms. Sweeney and her family were active members at First Baptist Church South Inglewood where Ms. Sweeney’s paternal uncle was the presiding minister. Ms. Sweeney found her place in the youth choir, a role she kept for many years. In one of her earliest stage performances, Ms. Sweeney’s mother added her to the church’s Sunday program, unbeknownst to Ms. Sweeney. Ms. Sweeney nervously took the stage in front of the congregation, but once she played the first note the nerves fled her body, and what remained was the talent that she had honed for so many years.[7]

[1] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[2] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[3] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[4] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[5] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[6] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[7] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

Performance and Growth

Ms. Sweeney’s love of performance followed her into her teenage years where she continued her passion and talent for the violin. In addition to participating in her school’s music program, Ms. Sweeney was a member of the Nashville Children’s Symphony and the Nashville Community Orchestra. However, her most impactful membership came from her involvement with the Cremona Strings Orchestra.[1]

The Cremona Strings Orchestra was a group “composed of students, ages seven to seventeen, from eleven Metro schools,” founded by Robert “Bob” Holmes. [2] Holmes goal was to teach African American children to play string instruments, specifically the violin, the viola, the cello, and the bass. In the mid1960s while Nashville schools were still segregated, Holmes went before the school board to request funding for his new initiative.[3] The members of the school board told Holmes that Black children “didn’t have the capacity to learn.”[4] Unperturbed, Holmes set out to prove them wrong and by the end of the 1960s the Cremona Strings Orchestra had grown to a group of over thirty students who presented concerts that included “popular hits, along with several other special compositions.”[5] The orchestra often played local events, joining the Pearl Senior High School Chorus for their annual Spring Concert in April of 1969.[6] Later that year, the thirty-piece orchestra played their first annual concert at the Fisk University Chapel. An article published by The Nashville Tennessean leading up to the event states, “The orchestra, which is directed by Robert Holmes, has appeared on numerous television and radio programs throughout the southeast and is preparing to do its first TV special for a local television station.”[7] Looking past short-term growth and local events, Holmes stated, “Our future plans after the concert include establishment of a scholarship fund and sponsoring all members of the orchestra in music schools this summer.”[8] Her work with the orchestra would help solidify her skills.

Figure 14. Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney photographed when she was a child. (Michael Kevin Neal, Personal photograph, “Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney solo portrait,” Date unknown.)

[1] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[2] “Marathon Raises Fund for Orchestra,” The Nashville Tennessean (Nashville, TN), August 12, 1968.

[3] Cindy Carter, “Cremona Strings: Children and Parents Learning to Play Together,” YouTube video, 6:18, January 6, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_1AVg833HGU.

[4] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[5] “Orchestra Sets Concert At Fisk Chapel,” The Nashville Tennessean (Nashville, TN), May 11, 1969.

[6] “Pearl Concert To Feature School Chorus,” The Nashville Tennessean (Nashville, TN), April 6, 1969.

[7] “Orchestra Sets Concert At Fisk Chapel,” The Nashville Tennessean (Nashville, TN), May 11, 1969.

[8] “Orchestra Sets Concert At Fisk Chapel,” The Nashville Tennessean (Nashville, TN), May 11, 1969.

“There’s A Place For Us”

While continuing to play the violin, Ms. Sweeney discovered a love for the performing arts. In 1968, Ms. Sweeney found herself center stage as Maria in a summer production of the acclaimed musical West Side Story, a modern interpretation of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet whose movie adaptation had won the Academy Award for Best Picture just 6 years prior.[1] As Ms. Sweeney stated, “In Nashville, they had what they called summer theater for . . . two or three years . . . These were federally funded musical productions, and they happened on each side of town . . . and these were productions that drew students together in a particular area and they would pay us.”[2] With over 250 students participating, the Summer Drama Program was sponsored by the Metro Nashville Public Schools System and relied on federal funding through Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act. [3] The program was furnished with $25,000 to produce three shows for the community in each of the county’s three school districts, including Charlie’s Aunt for District I, Wildcat for District II, and West Side Story for District III.[4] In 1967, the previous year, all three districts produced a single production of Rodger and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma.[5] The Summer Drama Program targeted students from “mainly hard core poverty areas of the city” that the federal government designated “culturally deprived, many of [the performers] from homes with less than $2,000 annual income.”[6]

In the eight weeks leading up to the ensemble’s first performance, Ms. Sweeney traveled to Washington Junior High School for five days a week. Along with a group of 125 other students, she rehearsed for four hours in the grueling heat of the school’s auditorium.[7] Ms. Sweeney and the other performers were “paid a $5 stipend weekly to cover costs of lunches and bus fare.”[8] In an article written by Sandra Stephens for The Nashville Tennessean titled “These ‘West Side’ Players Live Their Parts,” 14-year-old Ms. Sweeney, going by her middle name Jo Ann, said that the characters were easier to understand and identify with adding, “I think all the people in the cast fit their roles very well.”[9] On August 8th, after all the performances throughout the county were completed, all participating students gathered at Rose Park Junior High School to celebrate their accomplishments. On that night, Mrs. Katie Lawrence, Pearl High School instructor and West Side Story Director, presented Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney with the award for Best Actress – a triumphant conclusion to months of hard work.[10] Reflecting on her time in Summer Drama Theater, Ms. Sweeney said, “Those are the kinds of things that the government used to make happen for us, for school kids, and it kept us busy and kept us out of trouble.”[11]

Like the lyrics of “Somewhere” from West Side Story say, “There’s a place for us / Somewhere a place for us,” Ms. Sweeney spent her adolescence in places where her passions and her talents merged into something meaningful that provided a sense of community and belonging. However, growing up in the south at the height of the Jim Crow Era was not easy.

Figure 15. Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney is pictured in front portraying Maria in West Side Story. (Sandra Stephens, “These ‘West Side’ Players Live Their Parts,” The Nashville Tennessean (Nashville, TN), July 28, 1968, page 10.)

[1] “The 34th Academy Awards: 1962,” Oscars (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences), accessed September 21, 2022, https://www.oscars.org/oscars/ceremonies/1962.

[2] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[3] “Summer Theater Youths Honored,” The Nashville Tennessean (Nashville, TN), August 10, 1968.

[4] Sandra Stephens, “These ‘West Side’ Players Live Their Parts,” The Nashville Tennessean (Nashville, TN), July 28, 1968, 10.

[5] Stephens, “These ‘West Side’ Players Live Their Parts.”

[6] Stephens, “These ‘West Side’ Players Live Their Parts.”

[7] Stephens, “These ‘West Side’ Players Live Their Parts.”

[8] Stephens, “These ‘West Side’ Players Live Their Parts.”

[9] Stephens, “These ‘West Side’ Players Live Their Parts.”

[10] “Summer Theater Youths Honored,” The Nashville Tennessean (Nashville, TN), August 10, 1968.

[11] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

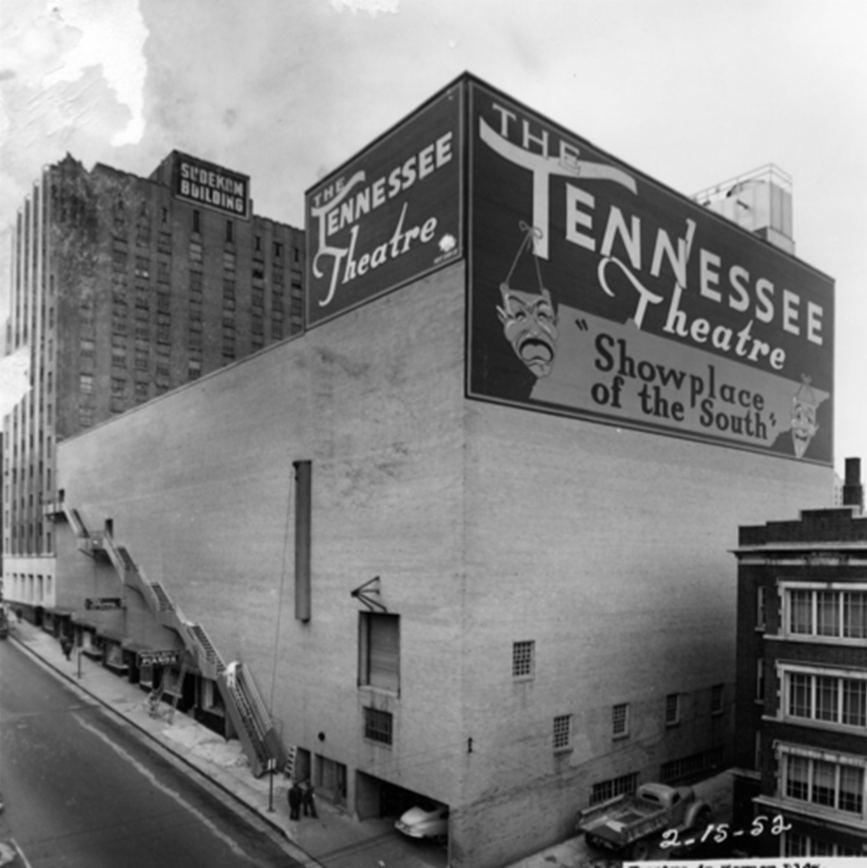

Up The Side Stairwell

At its height, The Tennessee Theatre, located in the heart of Nashville’s shopping district, was advertised as the “Showplace of the South” with the bright bulbs adorning its marquee and its lobby adorned with bas-relief sculptures and a plush carpet. In 1988, the building was dismantled and demolished.[1] However, if it still stood what would likely remain is not just the remanence of Nashville’s entertainment past, but Jim Crow era architecture that ensured the enforcement of segregation. Some of Ms. Sweeney’s earliest memories included sitting in the Tennessee Theatre’s “crow’s nest,” the balcony portion of the theatre designated for Black patronage. As Ms. Sweeney recalls, “Blacks could not enter the front door. We had to enter to the side and go up the stairwell on the outside.”[2] The photo from the Nashville Public Library’s Digital Collection shows the stairwell used to access the segregated balcony (Figure 16).

Figure 16. The Tennessee Theatre as viewed from Sixth Avenue. See, Nashville Public Library Digital Collections. Nashville: Metropolitan Nashville/Davidson County Archives, 1952. Nashville Public Library. Retrieved from https://digital.library.nashville.org/digital/collection/nr/id/9069 (22 January 2022)

As an African American growing up in a segregated society, Ms. Sweeney’s experiences were typical. She recalled being forced to use the colored restroom in the basement of a department store, denied service from certain lunch counters and restaurants, asked to move to accommodate White patrons, and called racial slurs. When Nashville emerged as a major touchstone for the Civil Rights Movement, Ms. Sweeney, too young to get involved, watched with pride from the sidelines as her three older brothers, who attended Fisk University at the time, participated in the city’s earliest sit-ins and protests – actions that would lead to their arrest. Constant news coverage, her brothers’ participation, and Ms. Sweeney’s growing awareness of racism meant ongoing conversations between Ms. Sweeney and her parents. Ms. Sweeney stated, “I understood what was going on. What didn’t make sense to me was, why? I didn’t understand why things had to be that way, but I understood that they were that way. My parents were actually proud of my brothers for taking part [and] being agents of change.”[3]

When Ms. Sweeney turned thirteen, her mother gave her “permission to ride the bus alone.”[4] One day, she rode the bus downtown to one of the many department stores with the intention of purchasing a pair of shoes. After settling into the shoe department and getting assistance from the shoe salesman, she was given a pair of shoes to try on. Once she slipped them on her feet, she recognized her mistake – she had asked for the wrong size. Thinking nothing of it, she put them back in their accompanying box and informed the salesman of her mistake. It was at that point that she was informed that, regardless of their fit, she would be required to purchase the shoes because she had already tried them on. Ms. Sweeney recalled this moment saying, “It was just humiliating to be told that because I tried on a pair of shoes, and because I’m Black, I had to buy them, and it doesn’t matter . . . They took away my option to get the right size of shoe, and I was very angry.”[5]

A year later, Ms. Sweeney’s family turned on their family television and heard the news that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated. “I do remember it like it was yesterday,” Ms. Sweeney said recalling the historic night. She continued saying, “I remember when it was announced on the news, and then not many minutes later I remember hearing the sound of glass being broken. We all went to the back window, and we could look and see where somebody was throwing rocks and breaking out the glass in this guy’s store . . . I remember the riots and the protests and everything.”[6] The news of Dr. King’s death “dashed the hopes of Black Americans for the commitment of White America to racial equality,” and growing frustrations lead to civil disturbances nationwide.[7] Nashville was no exception. The following day, The Nashville Tennessean’s headline read in bold letters “Dr. King Slain In Memphis,” and the paper showed images of National Guardsmen navigating the city’s streets with tanks and reports of rock-throwing that “escalated into gunfire and scattered looting which continued at midnight.”[8] Remembering what that night felt like, Ms. Sweeney said, “It was heartbreaking . . . I remember that feeling of, ‘Who’s going to lead us now? What do we do?’” [9]

In September of 1971, Ms. Sweeney was preparing for her senior year of high school. Across town at the Tennessee State Fairgrounds, Casey Jenkins, just coming off his failed run for Nashville Mayor, was hosting a meeting of more than 15,000 members of the Concerned Parents Association, a coalition of parents against court-ordered busing scheduled to start in the upcoming school year. Jenkins was calling for a countywide boycott of Nashville schools and encouraging parents to keep their children at home. Additionally, he encouraged outraged parents to join him on the first day of school protesting the flood of incoming students.[10] It was the protestors from her first day of school that Ms. Sweeney recalled vividly saying, “When that bus pulled up in front of the school, there were all these White parents out there with signs calling us the ‘n’ word and protesting . . . so we had to get off the bus and walk past all of that.”[11] Ms. Sweeney, as a result of newly enforced federal laws, was forced to leave Pearl High School, located just a few blocks from her home, and ride the bus thirty to forty minutes to Hillwood High School, located in the historically White neighborhood of Belle Meade. The New York Times reported that “with attendance at 81 and 76 per cent on the first two days, many Whites seemed to be keeping their children out of schools when longer bus rides were involved while Blacks seemed to be complying.”[12] Ms. Sweeney joined many other African Americans who complied with the new regulations while many Whites kept their children at home. Ms. Sweeney recalled arriving at the school to mixed emotions from teachers and students with some going out of their way to express kindness to their newest students and colleagues while others would only greet them with cold stares.[13] Ms. Sweeney recognized immediate differences between Pearl and Hillwood saying, “Things were better because our books weren’t used and scribbled on, and you go to White schools and those books were brand new. You could smell them, it smelled new.”[14] Even with some positive interactions and better resources, Ms. Sweeney said, “I knew instantly that that wasn’t the environment that I wanted to stay in. If there was any way that I could get out of it, I wanted to.”[15] Ms. Sweeney returned to Pearl during her senior year with a tactic that she saw other kids using recalling, “I looked for classes that weren’t being offered at the other school. I used that as a reason to get back to Pearl High School, because there were some classes that the inner-city schools offered that weren’t being offered in the White schools outside the city limits.”[16] She graduated from Pearl High School the following spring (Figure 17).[17] While Ms. Sweeney was finishing her senior year, Eddie Miller was searching for his next star.

Figure 17. Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney posing in her cap and gown ahead of graduation from Pearl High School. (Michael Kevin Neal, Personal photograph, “Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney high school graduation portrait,” 1972.)

[1] “‘Tennessee’ Coming Down,” The Tennessean (Nashville, TN), December 14, 1988.

[2] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[3] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[4] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[5] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[6] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[7] “Mourning the Death of Martin Luther King Jr.,” National Museum of African American History and Culture, February 3, 2020, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/mourning-death-martin-luther-king-jr.

[8] Jimmy Carnahan and Jerry Thompson, “Dr. King Slain In Memphis: Guard Seals, Patrols North Nashville Area,” The Nashville Tennessean (Nashville, TN), April 5, 1968.

[9] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[10] George Vecsey, “Court-Ordered Busing Arrives in Nashville,” The New York Times (New York, NY), September 17, 1971, 45.

[11] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[12] Vecsey, “Court-Ordered Busing Arrives in Nashville,” The New York Times.

[13] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[14] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[15] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[16] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[17] Pearl High School: 1898-1983 Graduates (Nashville: Pearl High Alumni Association), 242.

“A New Country Look”

A camera bulb flashed as Linda Martell stood next to Bill Monroe backstage at the Ryman Auditorium (Figure 18). It was the summer of 1969, and Martell was preparing to take the stage of the world-famous Grand Ole Opry. That night Linda Martell made history as the first Black female solo country artist to perform on the iconic stage – a moment that signaled the upward trajectory of Martell’s fresh career.[1] The following year Martell released her debut album titled Color Me Country. Martell’s relationship with Plantation Records producer Shelby Singleton soon soured and Martell’s career was over as quickly as it started; however, Linda Martell left a hole that other managers and producers hoped to fill.

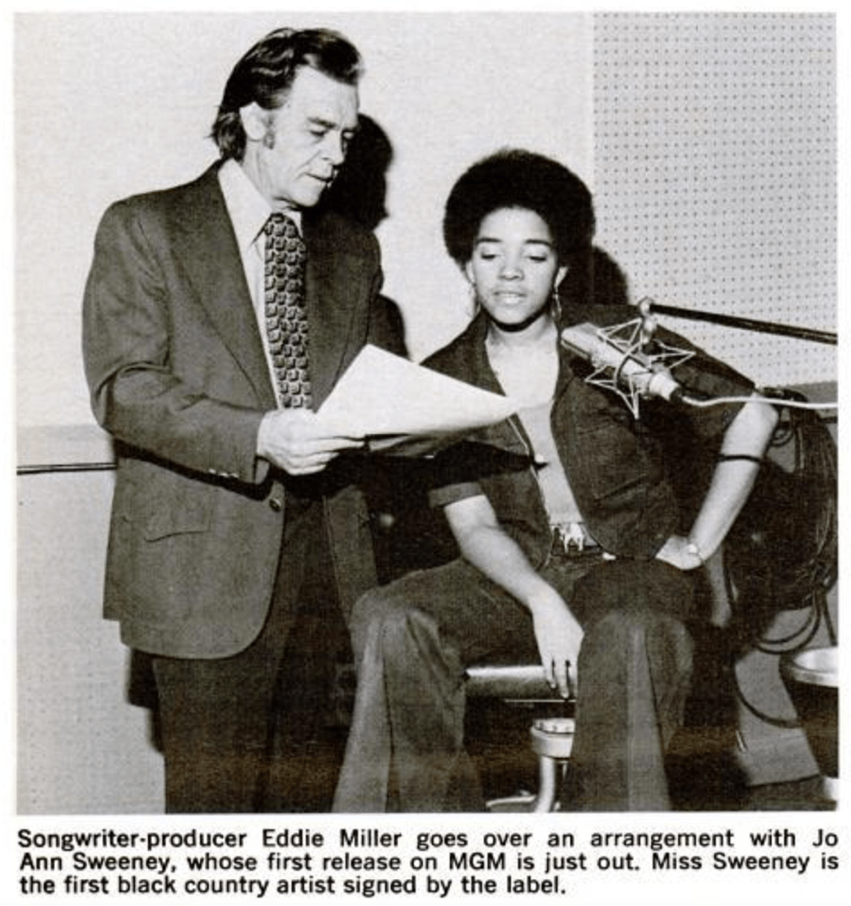

In 1972, Eddie Miller joined other music producers in “expressly seeking Black women who might become the female complement to Charley Pride,” and who could take the place of Linda Martell. Miller was a well-established singer-songwriter who had recently relocated to Nashville from Southern California in 1967. [2] Miller was known primarily for the commercial success of “Release Me (And Let Me Love Again),” a song that he helped pen in 1949 that quickly grew in popularity – a song that is now considered “an all-time country standard.”[3] His commercial success and notoriety on Music Row led him to establish Miller-Holt Productions where he represented other artists and continued to write songs. In 1972, he began representing Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney; however, accounts of how Ms. Sweeney’s career started and how she initially met Eddie Miller all differ slightly.[4]

Figure 18. Linda Martell poses next to Bill Monroe before performing on the Grand Ole Opry. (Photographer Unknown, Linda Martell and Bill Monroe backstage at the Ryman Auditorium, August 1969, Black and White Negative, 5.67 x 5.71 cm, Digital Collection, Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, Nashville, Tennessee, https://digi.countrymusichalloffame.org/digital /collection/photo/id/60392/rec/6)

Ms. Sweeney remembered meeting Eddie Miller for the first time in the Pearl High School band room. “I don’t know who he talked to, but somebody recommended that he come and talk to me for the purpose of becoming a recording artist in the field of country and western music, a Black female recording artist,” Ms. Sweeney recalled. This proposition came as a shock to Ms. Sweeney, who couldn’t imagine a pathway to success for herself country and western music. “Of all things, country and western. I like the stuff but come on.”[5] An intrigued Ms. Sweeney asked Miller to discuss this with her parents, “I remember distinctly my dad looked at me [and] said, ‘Can you sing country?’” to which Ms. Sweeney replied, “I’d be glad to try.”[6]

Ms. Sweeney’s decision to record country music was risky. As stated by Rolling Stones writer David Brown, “Black contributions — from the banjo to string music to the harmonica — were among the building blocks of country music, but Black singers had, by the Sixties, made few inroads into the genre . . . And the few Black artists who had consistent hits in country . . . were men.” [7] Ms. Sweeney recalled deliberating the risks that inevitably would follow success. “I think because of the era, my first concern was how well would it go over? Because it was certainly nothing common. If I were doing R&B or something like that my attitude about it would’ve been different. But I immediately started thinking, ‘Well, what if this does happen? What about when I have to go on the road and make personal appearances? What’s going to happen then? How am I going to be treated? What’s going to be the attitude?’ That’s what was going through my mind. I had concerns about that. You have to remember that the Voting Rights [Act] had only been passed only five years before this happened. So that was my main concern. ‘Would I have to go through the back doors and go through the kitchen instead of the front door?’”[8]

Reporting on her discovery, Billboard magazine reported that Ms. Sweeney, shortening her name to just Jo Ann Sweeney, was “found singing in a Baptist Sunday school choir.”[9] Though Ms. Sweeney had performed in her church choir for many years, Ms. Sweeney’s account does not mention meeting Miller prior to that day at Pearl High School. Though this could have been a simple error, the inclusion of Ms. Sweeney’s “serendipitous discovery” fits a common trope designed to create an “authenticating narrative” around early Black artists attempting to integrate country music.[10] Charley Pride’s rise to fame was similarly characterized and Linda Martell was known to have begun “singing in the Baptist church as a child.”[11] Historian Diane Pecknold that Ms. Sweeney’s random discovery is “a narrative entirely at odds with the fact that her father, Jimmy Sweeney, was a songwriter for Acuff-Rose and recorded frequently on Music Row.”[12] Though her father continued to write music well into Ms. Sweeney’s life, Ms. Sweeney did not mention receiving her father’s assistance when kickstarting her career. Contrarily, Ms. Sweeney recalled never seeing her father perform live and described being caught off guard by the prospect of a career in country and western music.[13] Eddie Miller’s sponsorship of Ms. Sweeney was an important factor in determining the commercial success, publicity, and promotion that surrounded her country music career. On this topic, Diane Pecknold wrote, “While the presence of Black artists on Music Row was certainly conventional, it nonetheless depended on their relationships with the White entrepreneurs who controlled the industry, and those relationships were inevitably infected with White hegemony.”[14] When Ms. Sweeney entered the realm of country music recording, success was determined by a hierarchy that placed White men at the top. Ms. Sweeney began a career in an industry built on systemic prejudices that added negative pressure to the success of women of color. It is likely that executives would have been indifferent to Ms. Sweeney’s father’s previous successes.

[1] David Browne, “Linda Martell: Country’s Lost Pioneer,” Rolling Stone (Rolling Stone, September 2, 2020), https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/linda-martell-Black-country-grand-ole-opry-pioneer-1050432/.

[2] “Release Me Writer Eddie Miller Dies,” The Tennessean (Nashville, TN), April 12, 1977, 9.

[3] “Eddie Miller,” Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame, accessed September 21, 2022, http://nashvillesongwritersfoundation.com/Site/inductee?entry_id=2530.

[4] “Miller Sets 2 MGM Acts,” Billboard, November 1972

[5] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[6] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[7] Browne, “Linda Martell: Country’s Lost Pioneer.”

[8] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[9] “Miller Sets 2 MGM Acts,” Billboard, November 1972.

[10] Diane Pecknold and Kristine M. McCusker, Country Boys and Redneck Women: New Essays in Gender and Country Music (Jackson: The University Press of Mississippi, 2016), 148.

[11] Pecknold and McCusker, Country Boys and Redneck Women, 148.

[12] Pecknold and McCusker, Country Boys and Redneck Women, 163.

[13] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[14] Pecknold and McCusker, Country Boys and Redneck Women, 150.

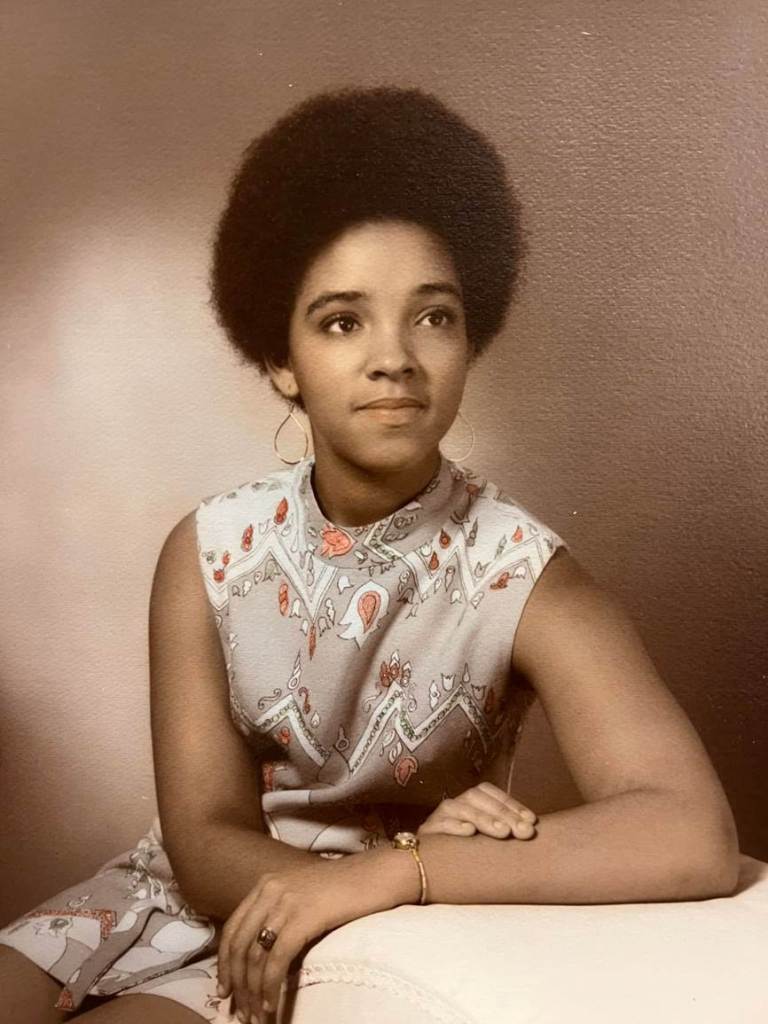

An Afro and Big Hubcap Earrings

In 2004, Ms. Sweeney sat on a panel alongside other musicians and producers to discuss her father’s career; however, at one point the conversation turned to Ms. Sweeney’s own career. In this interview, Ms. Sweeney recalls a moment when Eddie Miller asked if she would be comfortable wearing a wig in an upcoming promotional photoshoot. Ms. Sweeney recalled, “I was righteously indignant. I was wearing an Afro and big hubcap earrings and I didn’t want to part with that . . . I said absolutely not, I cannot do that. But it didn’t stop anything. We went ahead and did the photo session and the whole thing went very, very well. He was very enthusiastic about it.”[1] These photos were used sparingly to promote Ms. Sweeney’s releases (Figures 19, 20, and 21). This interaction points to a professional dynamic where Ms. Sweeney had some control over the early direction of her career, a benefit that was not present for the Black artists that preceded her. Diane Pecknold writes that because Ms. Sweeney’s “father had worked with Music Row producers and publishers for years . . . [Ms. Sweeney] enjoyed a social position there that did not depend on Miller alone.”[2] This point could be further supported by the previously cited Billboard magazine article.

Just a few sentences after the line about Ms. Sweeney’s discovery, the article states, “Miss Sweeney had been around sessions of all sorts for a long while. She played violin as a studio musician.”[3] However, these early studio sessions, like her relationship to her father’s career, were not something Ms. Sweeney mentioned while recounting the process of establishing her career. The contents of the Billboard article were likely developed from information exclusively provided by Eddie Miller or Miller-Holt Productions more generally. Recognizing the need to legitimize Ms. Sweeney as a serious artist, Eddie Miller understood that how he framed her to the press and, subsequently, how the press presented Ms. Sweeney to the public was important to her commercial success. The assumption that Ms. Sweeney was well-connected within the music industry appears to be rooted in the idea that Ms. Sweeney’s inherent bona fides were not enough to sell her, as a Black female, to country music listeners and the industry more broadly. Ms. Sweeney’s memory reflects her view that, independent of previously existing professional connections and familial ties to Music Row, she built something unique that had only been attempted by a handful of others.

Whether their meeting was spontaneous or well-planned, Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney agreed to be represented by Eddie Miller via Miller-Holt Production Co. Later that year, Ms. Sweeney signed a record deal with MGM Records becoming “the first Black country artist signed by the label.”[4] Pam Miller, Eddie Miller’s daughter who was also eighteen years old, joined the label alongside Ms. Sweeney. To help her prepare, Miller gave Ms. Sweeney a set of demo tapes that Pam had previously recorded and was told to listen to her inflections. “I really wasn’t sure if I could pull it off,” Ms. Sweeney recalled.[5] Ms. Sweeney took the recordings and, adding her own stylistic choices, turned each track into something new. Before long, Ms. Sweeney was ready for the studio.

Figure 19. Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney poses next to Eddie Miller in a promotional photograph published in Billboard magazine. (“Miller Sets 2 MGM Acts,” Billboard, November 1972)

Figure 20. Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney appears in a promotional photograph for MGM Records. (Michael Kevin Neal, Personal photograph, “Promotional headshot of Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney,” August 1972.)

Figure 21. Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney appears in a promotional photograph for MGM Records. (Michael Kevin Neal, Personal photograph, “Promotional headshot of Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney,” August 1972.)

[1] “Let’s Trade a Little: The Country-R&B Connection,” March 27, 2004 (DVD), Frist Library and Archive, Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, Nashville.

[2] Pecknold and McCusker, Country Boys and Redneck Women, 163.

[3] “Miller Sets 2 MGM Acts,” Billboard, November 1972

[4] “Miller Sets 2 MGM Acts,” Billboard, November 1972

[5] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

Bradley’s Barn

Ms. Sweeney, looking out of the car window, saw Nashville’s urban landscape melt away, replaced with farmland. She finally arrived to what she could only recall as “The Barn” stating, “It was way out in the middle of nowhere . . . like one of those outlying places.”[1] Ms. Sweeney was likely referring to Bradley’s Barn, a studio founded by Owen Bradley, an “architect of the Nashville Sound.”[2] In 1964, Bradley passed the fully-functioning barn on the way to his favorite boat dock. [3]

By 1965, Bradley had traded the cattle, horses, and feed for state of the art equipment building a studio that some called “the eighth wonder of the music world.” [4] When Ms. Sweeney arrived on the 68 acre property, Owen Bradley had a long record of producing hits for country and western artists including Roy Orbison, Ernest Tubb, Webb Pierce, Bill Anderson, Marty Robbins, Ferlin Husky, and Conway Twitty. [5]

With numerous Top Ten hits for Kitty Wells, twelve Top Ten hits for Brenda Lee, over fifty hits for Loretta Lynn, and collaborations with Patsy Cline that became the standard for the recording industry, Bradley had proven a keen ability to produce some of country music’s most popular female voices, something that would be an asset for Ms. Sweeney.[6] At the time, Bradley’s Barn was “one of the most sought after sites for recording,” and Ms. Sweeney’s session would have been just one of the studios 15 weekly sessions. [7] Ms. Sweeney recalled recording her tracks LA style where “the musicians, the lead vocalist, and the backing vocals are all in the room at the same time, and they record all at once.”[8] In these sessions, Ms. Sweeney recorded six songs that include, in the order of their release, the following:

- “I’ll Take It”

- “Think It Over Carefully”

- “Rocky Top”

- “Reachin’ For You”

- “‘Till Sunrise”

- “A World Without You”

[1] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[2] “Owen Bradley,” Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, September 16, 2022, https://www.countrymusichalloffame.org/hall-of-fame/owen-bradley.

[3] “Bradley’s Barn: Nashville Sound In A Country Setting,” Ampex Case Histories, Date Unknown.

[4] “Bradley’s Barn: Nashville Sound In A Country Setting,” Ampex Case Histories, Date Unknown.

[5] “Owen Bradley,” Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, September 16, 2022.

[6] “Owen Bradley,” Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, September 16, 2022.

[7] “Bradley’s Barn: Nashville Sound In A Country Setting,” Ampex Case Histories, Date Unknown.

[8] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

Promotion

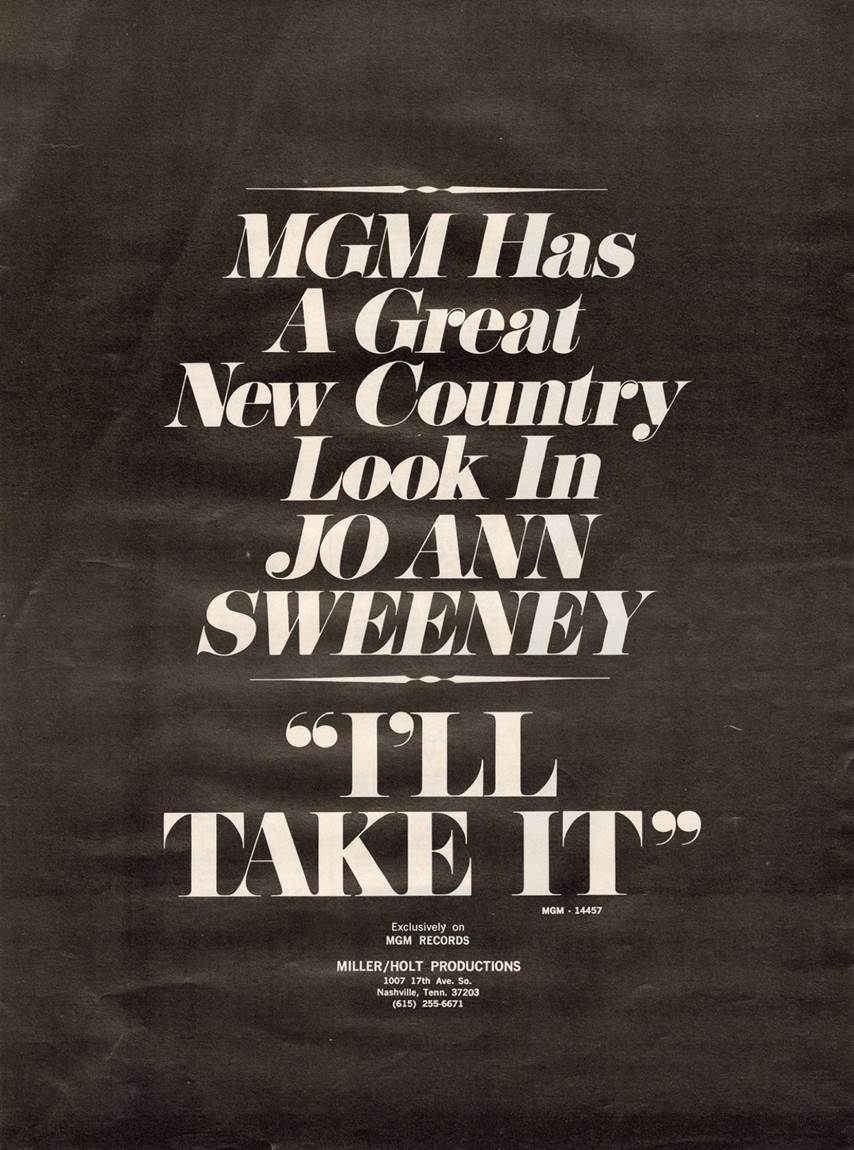

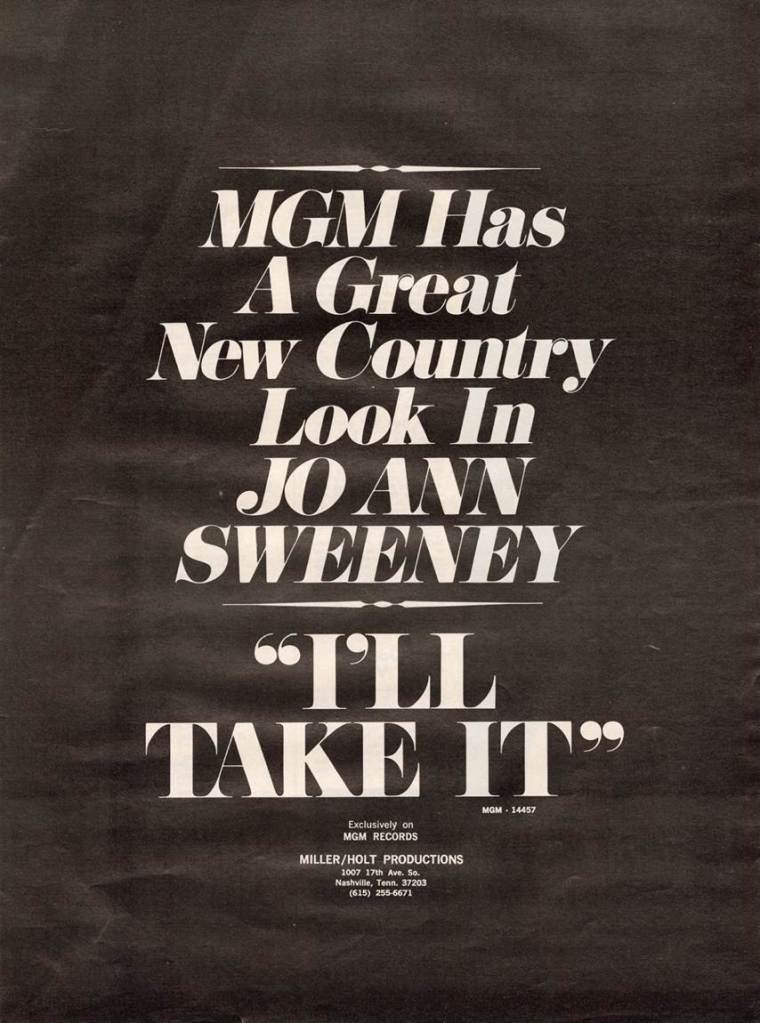

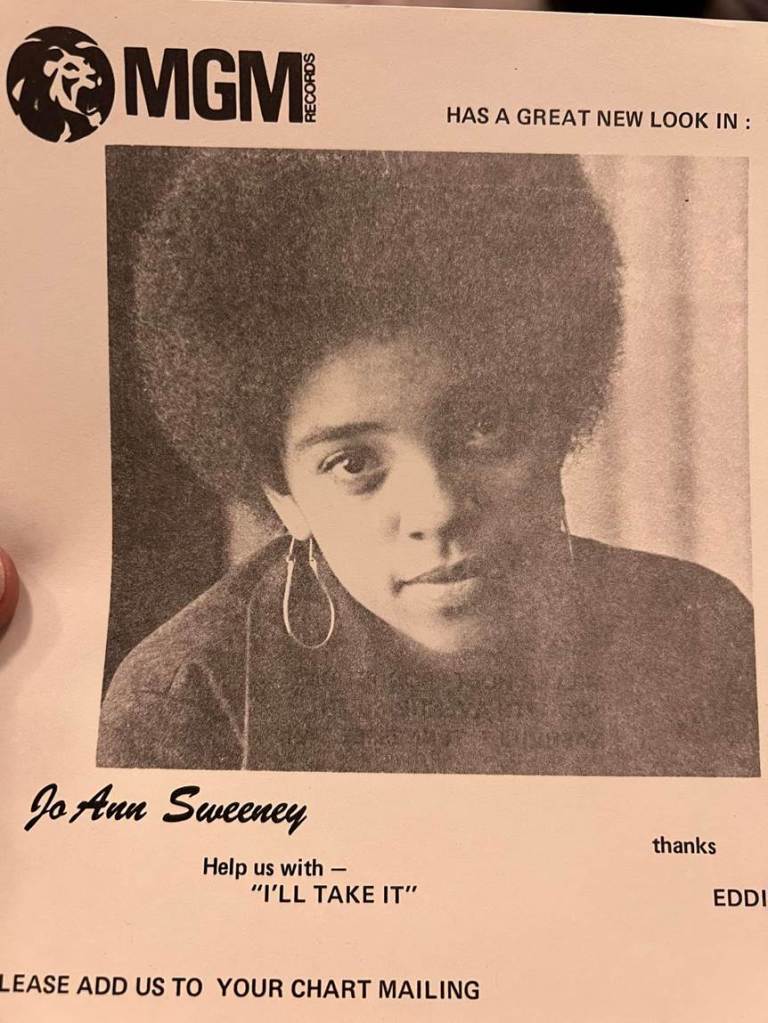

These songs were released as three 45 RPM records. “I’ll Take It” was released in 1972 with “Think It Over Carefully” on the records B-side. Promotion for all of the records was scarce and “I’ll Take It” was the only one of Ms. Sweeney’s singles that received full-page, paid advertisements. One advertisement was placed in the November 25, 1972 issue of Billboard magazine reading “MGM Has A Great New Country Look In Jo Ann Sweeney” with “I’ll Take It” written below (Figure 22).

Figure 22. Advertisement published in Billboard magazine promoting Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney’s single “I’ll Take It.” (“MGM Has A New Country Look In Jo Ann Sweeney,” Billboard, November 1972.)

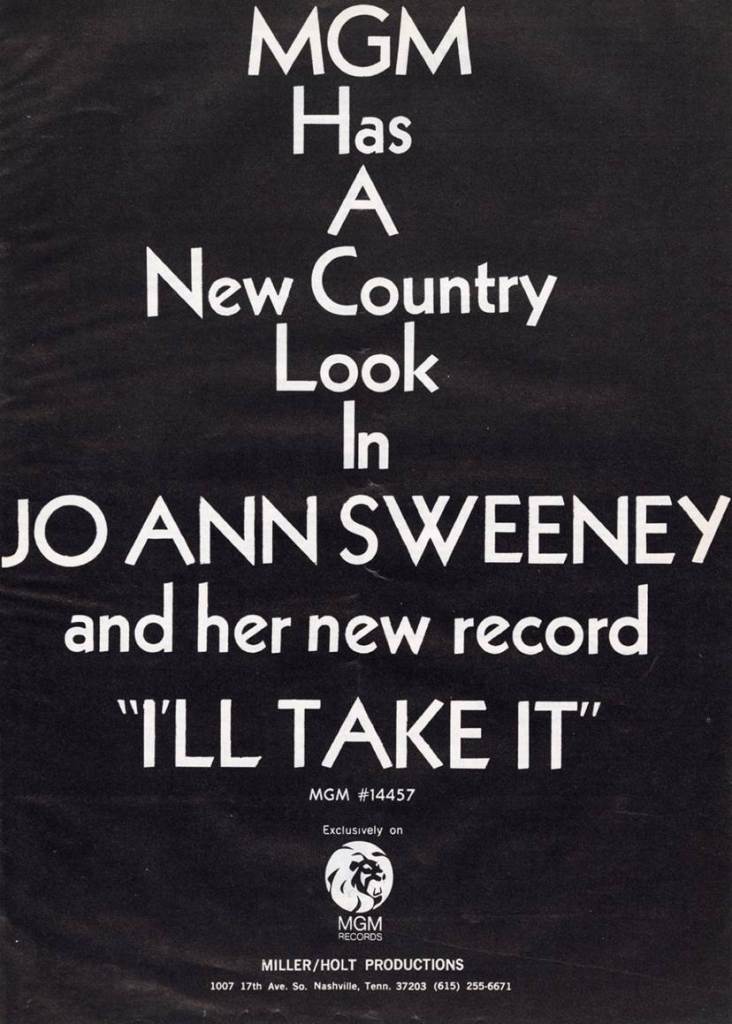

A second advertisement was placed in the December 9, 1972 issue of Cashbox magazine and read “MGM Has A New Country Look In Jo Ann Sweeney and her new record ‘I’ll Take It’” followed by the MGM Records logo (Figure 23). Both advertisements have a Black background with the text written in bold, White letters followed by the contact information of Miller-Holt Productions. Photographs from the earlier photoshoots, showing images of Ms. Sweeney were excluded from these public facing promotions.

Figure 23. Advertisement published in Cashbox magazine promoting Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney’s single “I’ll Take It.” (“MGM Has A New Look In Jo Ann Sweeney and her new record,” Cashbox, December 1972.)

New Releases

Though “I’ll Take It” does not appear on any of the top country music charts, it was followed by the spring 1973 release of “Rocky Top” with “Reachin’ for You” taking the records B-side. Recorded for the first time just five years prior to Ms. Sweeney’s release, “Rocky Top” was penned by popular country songwriting duo Boudleaux and Felice Bryant and is “now an official Tennessee state song and the fight song for the University of Tennessee’s athletic teams.”[1] An article published in the March 3, 1973 issue of Billboard states, “The great Boudleaux Bryant hit ‘Rocky Top’ has been recorded again, this time by Black artist Jo Ann Sweeney on MGM.” The article continues saying, “The young lady gives it a new twist. It has sold well for everyone who has recorded it.”[2] The article suggests that Ms. Sweeney was the first Black artist to record the song.

Finally, “‘Till Sunrise” was released, with “A World Without You” taking its place on the records B-side, in September of 1973. Even with little to no apparent promotion, the single took a spot in Billboard’s Top Single Picks in the Country category the week of September 1st.[3] Just one week later, Billboard reported that “Eddie Miller and his MGM stable, including Pam Miller, Jo Ann Sweeney, and Don Holiman for [Miller-Holt] Productions,” were being represented abroad on a music and television executives’ trip to Australia, Hong Kong, and Japan.[4] This not only means that, to some degree, Ms. Sweeney’s music was actively being promoted, but it confirms her continued space on Miller’s growing MGM roster.

Ms. Sweeney remembered sending promotional packages to area disc jockeys. These packages included a note from Eddie Miller that stated, “Help us with ‘I’ll Take It’ . . . Please add us to your chart mailing” (Figure 24). This note was paired with a photo of Ms. Sweeney, something she says hindered the success of the records. “They were good records. I would’ve purchased one, and I think that my race had a lot to do with it, because when you send out those packets . . . they probably took one look at it and tossed it in a waste basket. That’s what I truly believe.”[5] The relationship between Eddie Miller and Ms. Sweeney quickly dissolved. “After I recorded those 45s, I never heard from those [him] again. But I also know that he had a daughter who took precedence over what he was doing. His daughter was also trying to get her recording career off the ground and I’m going to assume that he just turned all of his attentions to her.”[6] Being signed to MGM at the same time as Ms. Sweeney, Pam Miller was trying to make a name for herself in country and western music.

Alongside Ms. Sweeney, Ms. Miller released four songs through MGM between 1972 and 1973. Ms. Miller went on to record four full-length albums throughout the 1970s and 1980s which were released via Memphis Gospel and Country label, Starlite.[7] Whether it was because of race, Eddie Miller’s shifting focus, or personal access to connections and wealth, Ms. Miller and Ms. Sweeney experienced starkly different careers. Ms. Sweeney’s final solo record was released in 1974 via Nugget records and featured “song title” on the A-side and “song title” on the B-side. When asked about this record, Ms. Sweeney stated, “Nugget? That doesn’t ring a bell with me.”[8] For all of her solo recordings, Ms. Sweeney never received any compensation. “Maybe it didn’t take off or go to number one with a bullet or chart or any of that, but I’m proud of it because it’s good, and that’s good enough for me. It was good stuff. I did it.”[9]

Figure 24. Promotional material sent to local disc jockeys to promote “I’ll Take It.” (Michael Kevin Neal, Personal photograph, “Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney high school graduation portrait,” 1972.)

[1] “Boudleaux and Felice Bryant,” Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, July 5, 2022. https://www.countrymusichalloffame.org/hall-of-fame/boudleaux-and-felice-bryant.

[2] Bill Williams, “Nashville Scene,” Billboard, March 1973.

[3] “Billboard’s Top Single Picks: Country Picks,” Billboard, September 1973.

[4] Bill Williams, “Nashville Scene,” Billboard, September 1973.

[5] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[6] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[7] “Pam Miller,” Discogs, accessed September 2, 2022, https://www.discogs.com/artist/3211702-Pam-Miller-4.

[8] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[9] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

After MGM

After her initial recordings at Bradley’s Barn, Ms. Sweeney went to college to study music, first at Fisk University then transferring to Tennessee State University. Ms. Sweeney met Michael Kevin Neal, Sr. in TSU’s Student Union Building in 1975.[1] The couple married on February 1, 1976, and the following year Ms. Sweeney gave birth to their first son, Michael Kevin Neal, Jr. Five years later, Ms. Sweeney gave birth to her second son, Chauncey Neal.

After taking a brief hiatus from her professional music career to care for her children, Ms. Sweeney returned to the studio, providing backing violin tracks. “I started doing a lot of backing singing and it was a pure fluke because I actually went in to do some recording as a [violin] musician and one of the singers did not show up and they needed someone who could sight read and fill in. So, I said, ‘Well, I can do it,’ . . . from that point, I started getting more and more work.”[2]

The earliest known record where Ms. Sweeney is credited as a backup vocalist is Marshall Chapman’s 1982 album titled Take It On Home.[3] In the song “The Perfect Partner,” Ms. Sweeney’s vocal riffs that can be clearly identified throughout the track. Take It On Home was the last album to be recorded in Owen Bradley’s Quonset Hut studio.[4] Before the building was closed and turned into office space and storage, the Quonset Hut studio saw recording sessions that included George Jones, Buddy Holly, Loretta Lynn, Johnny Cash, Patsy Cline, Marty Robbins, Bob Dylan, Dusty Springfield, and Brenda Lee.[5]

The studio was named for Owen and Harold Bradley’s addition of a Quonset Hut, “a large, prefabricated metal building with a curved roof that was used extensively by the military in World War II,” to the back of the existing property.[6] Owen Bradley operated the studio for twenty-five years and, now, the land where the studio once stood hosts Belmont University’s Mike Curb College of Entertainment and Music Business. Ms. Sweeney’s participation in Take It On Home made her one of the last musicians to perform in the famous studio, and gave her the opportunity, once again, to be a part of music history.

Ms. Sweeney continued singing backing vocals for dozens of artists in varying genres. She also sang in commercials for several products and fast-food restaurants, including McDonald’s, Burger King, Murray Bicycle, and Miss Goldy Chicken. “[It’s a] wonderful way to make money because when you do a jingle and it finds placement, it depends on how many markets, and every [few months] you get this nice fat check.”[7]

Many of Ms. Sweeney’s contributions as a backing vocalist have gone uncredited. At first, Ms. Sweeney participated in these sessions in the evenings while balancing a full-time job and raising her children. Eventually Ms. Sweeney left her job as an Administrative Assistant at Meharry Medical College to pursue her session work full-time. Ms. Sweeney moved away from her session work around 1994 and began working as a temporary employee on short-term positions.[8]

[1] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

[2] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, October 21, 2021.

[3] Liner notes for Marshall Chapman, Take It On Home, Rounder Records #3069, 1982, Vinyl.

[4] Liner notes for Marshall Chapman, Take It On Home, Rounder Records #3069, 1982, Vinyl.

[5] Sarah Stakes, “Quonset Hut Hosts Reunion Celebration,” Music Row, Music Row Enterprises, LLC, 30 June 2011, https://musicrow.com/2011/06/quonset-hut-hosts-reunion-celebration/

[6] Michael Kosser, How Nashville Became Music City USA: 50 Years of Music Row (Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corporation, 2006), 12.

[7] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, October 21, 2021.

[8] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, October 21, 2021.

Spiritual Awakening

In the mid-1990s, Ms. Sweeney faced significant difficulties in her personal life forcing her to take a brief hiatus from work and music. “I had some problems . . . had it not been for God, I wouldn’t be sitting here talking to you.”[1] During this time of introspection, Ms. Sweeney grew closer in her relationship to God, and used the difficulties she faced to grow stronger in her faith. “I got called to the ministry,” and, in 1998, Ms. Sweeney gave her first sermon.[2] In 2019, Minister Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney became an Associate Pastor at the church she had attended with her family as a child, First Baptist Church South Inglewood.

In 2005, Ms. Sweeney helped form Cremona Strings Ensemble Too, a musical ensemble designed to continue the work of Ms. Sweeney’s early mentor Robert Holmes. Building on Holmes’ legacy of service, Ms. Sweeney and other members of the original Cremona Strings Orchestra set out to perform Holmes’ original compositions and teach a new generation of string musicians.[3] Ms. Sweeney performed with the Cremona Strings Ensemble Too at locations across Nashville including the Tennessee State Museum, the Frist Art Museum, and the Nashville International Airport.[4]

From her earliest memories, Ms. Sweeney’s appreciation for music and raw talent was a driving force in her life, and the Cremona Strings Orchestra Too allowed her to regularly engage with the instrument that she was so passionate about. Ms. Sweeney’s contributions with the group are an indelible part of her legacy.

[1] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, October 21, 2021.

[2] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, October 21, 2021.

[3] “Cremona Strings Ensemble Too,” Now Playing Nashville, June 28, 2021, https://www.nowplayingnashville.com/organization/cremona-strings-ensemble-too/.

[4] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, April 22, 2021.

Legacy

When asked what she wanted her legacy to be, Ms. Sweeney said, “That I tried to treat everybody equally and that I passed that on to my children . . . and to make sure that I [gave] the best that I [could] before I depart this earth. I don’t want to leave here with people looking down to say that I was a mean, or unaccommodating . . . I don’t want that. I want my legacy to say that I was a decent, upstanding Christian woman. A good, example of Christianity . . . That is all I want.”[1]

On January 18, 2022, just one day before her sixty-eighth birthday, Minister Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney passed away. On January 28, 2022, Ms. Sweeney’s funeral services took place at First Baptist Church South Inglewood.[2] The service was attended by dozens of family members and friends, and the virtual recording of the service has since been viewed by over 1900 people. Among the slew of flowers and photos that surrounded her casket, was her violin – now silent.

[1] Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, oral history to Danny Harp, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, October 21, 2021.

[2] Obituary of Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney, The Tennessean (Nashville, TN), January 20, 2022.

Figure 25. Photograph of Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney. (Michael Kevin Neal, Personal photograph, “Eugenia JoAnn Sweeney solo photograph,” 1972.)